Overview

The earlier Parts of this report have explored the experiences of victim-survivors in depth, including how the experiences of child sexual abuse they shared with the Board of Inquiry affected their life at the time, and subsequently. As discussed in those earlier Parts of the report, the impacts of historical child sexual abuse extend beyond victim-survivors, to secondary victims and affected communities.

As well as sharing with the Board of Inquiry their experiences of child sexual abuse and its consequences, victim-survivors and secondary victims shared their thoughts, hopes and aspirations for support and healing. Many victim-survivors (and some secondary victims) who engaged with the Board of Inquiry had experience with support services and were willing to provide their reflections and insights about those services. Victim-survivors also spoke about their personal healing journey.

Under clause 3(d) of its Terms of Reference, the Board of Inquiry was required to inquire into ‘[a]ppropriate ways to support healing for affected victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected communities including, for example, the form of a formal apology, memorialisation or other activities’.1 Under clause 3(e) of its Terms of Reference the Board of Inquiry was also required to inquire into ‘whether there are effective support services for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools’, having regard to ‘other inquiries and reforms that have taken place since the historical child sexual abuse occurred’.2

Healing looks different for every person and can take many forms. Healing processes for victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected communities may include sharing experiences, receiving acknowledgement and apologies, and seeing institutions responsible for failing to guard against or enabling child sexual abuse take responsibility for what happened. Seeking justice, helping others and banding together as communities in response to historical child sexual abuse can also help individuals and communities to heal.

Engaging with and receiving support from services can also play an important role in helping people to heal; and, as Dr Joe Tucci, CEO, Australian Childhood Foundation, told the Board of Inquiry, a ‘mix of formal and informal supports is essential to meet the varying needs of victim-survivors’.3 While they are only one aspect of healing, support services may contribute to healing by delivering trauma-informed therapeutic supports, facilitating connection with victim-survivor peers, and providing practical supports to victim-survivors, such as financial assistance or help with navigating the justice system and other complex processes.4

The Board of Inquiry has listened carefully to the information and ideas people shared about their healing and support needs. While its Terms of Reference do not require the Board of Inquiry to address the full range of support needs people shared, the inquiry nevertheless acknowledges them.

This Part of the report explores what healing means for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools.

To address clause 3(d) of the Terms of Reference, Chapter 15, Perspectives on healing(opens in a new window), introduces the concept of healing and explores the different ways individuals and communities can heal from historical child sexual abuse. It recognises that support services are a component of this healing.

The following two chapters — Chapter 16, Where people can go for support(opens in a new window), and Chapter 17, Support needs and challenges(opens in a new window) — address clause 3(e) of the Terms of Reference. They examine existing support services for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools to inform the Board of Inquiry’s assessment of whether there are effective support services in place for this cohort.

Chapter 18, Looking to the future(opens in a new window) contains the Board of Inquiry’s recommendations about specific ways to support victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected communities of historical child sexual abuse in government schools to heal, including recommendations for improvements to support services for victim-survivors.

A note to readers

Experiences of victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members

Throughout this report, the Board of Inquiry shares information that reflects some of the experiences that victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members shared with the Board of Inquiry.

In this Part, the Board of Inquiry shares some of the experiences and perspectives of victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members who participated in the Lived Experience Roundtable. The perspectives of the Lived Experience Roundtable participants have informed the Board of Inquiry’s consideration of various issues relevant to this Part.

The Board of Inquiry is deeply grateful to the victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members who so courageously shared their experiences of child sexual abuse. The Board of Inquiry also acknowledges those victim-survivors who have chosen not to disclose their experiences of child sexual abuse, and may never do so, including those who are no longer with us.

The Board of Inquiry asked people who engaged with it how they wanted their information to be managed. Some wished to share their experiences publicly. Some wished to do so anonymously and others wished to do so confidentially. Where people shared their experiences anonymously, the Board of Inquiry has not included any identifying information in this report. Where people shared their experiences confidentially, the Board of Inquiry used this information to inform its work, but has not included it in this report.

In relation to those who wished to share their experiences publicly, in some cases the Board of Inquiry determined that it should anonymise the information they shared. This decision was made for legal or related reasons, including in order to avoid causing prejudice to any current or future criminal or civil proceedings.

The Board of Inquiry shares the experiences of victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members to create an important public record of their recollections. However, the Board of Inquiry has not examined or tested these accounts for accuracy or weighed whether there is enough evidence to support criminal or civil proceedings. The approach the Board of Inquiry has taken in this regard is consistent with its objectives and its Terms of Reference.5

The Board of Inquiry expresses its immense gratitude to all who contributed, in any way, to its work. Those who shared their experiences have shaped the Board of Inquiry’s general findings and recommendations and contributed to a shared understanding, among all Victorians, of the impact of child sexual abuse. The Board of Inquiry expects this report will reinforce the community’s commitment to better protect children from sexual abuse into the future.

Introduction Endnotes

- Order in Council, ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3(d).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3(e).

- Statement of Joe Tucci, 21 November 2023, 12 [58].

- See e.g.: Submission 29, Bravehearts, 3; Statement of Rob Gordon, 22 November 2023, 9 [41]; Private session 19; Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023.

Chapter 15

Perspectives on healing

Introduction

Clause 3(d) of the Board of Inquiry’s Terms of Reference required it to inquire into and report on ‘[a]ppropriate ways to support healing for affected victim-survivors, secondary victims, and affected communities including, for example, the form of a formal apology, memorialisation or other activities’.1

Victim-survivors made clear to the Board of Inquiry that healing is important to them. As one participant at the Board of Inquiry’s Lived Experience Roundtable said: ‘healing really is for us as survivors — it’s about changing the narrative, about making it a comfortable space to talk about. We have to have the conversation’.2

This Chapter introduces and explores concepts of healing, including individual and collective healing. It examines how victim-survivors can heal from the impacts of historical child sexual abuse, recognising that healing is a very personal experience and takes different forms. It also explores the different ways that secondary victims and communities affected by historical child sexual abuse can heal.

Understanding what healing means for different people is an essential part of considering the range of actions required to support people and communities affected by child sexual abuse to heal. These responses are discussed in Chapter 18, Looking to the future(opens in a new window).

Healing from historical child sexual abuse

This section explores concepts of healing, and how communities and institutions can support people to heal from historical child sexual abuse.

Concepts of healing

Healing can have different meanings depending on the context, including the form of trauma involved.

At an individual level, healing has been described as an active and multidimensional process that happens within a person, rather than something that can be done to them.3 It can include ‘making things right’4 and ‘restoring balance where wrong has been done’.5

There is growing recognition in the field of healthcare that the concept of healing, which involves holistic, patient-centric care, is as important as that of curing.6 Researchers have developed an ‘Optimal Healing Environments framework’ with four domains — internal, interpersonal, behavioural and external — that recognise healing extends beyond the individual.7 The framework supports patients’ healing ‘by addressing the social, psychological, physical, spiritual, and behavioral components of healthcare’.8

Much can also be learned from concepts of healing as understood by First Nations communities, which take a holistic view of the process that incorporates the individual, families and communities.

Professor Tom Calma AO, while serving as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, described healing as ‘a necessary response to address trauma experienced by individual[s] and communities’.9 Professor Calma further described healing as a process that is personal and requires different responses for different people.10 He expressed the view that healing is not only about an individual; it also includes families and communities.11

According to the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, healing ‘embraces social, emotional, physical, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of health and wellbeing’.12 Healing approaches in Aboriginal communities can support a reduction in the impacts of trauma and abuse, increase social connection, improve social and emotional wellbeing, and reduce suicide rates.13

When working as a registered psychologist at the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service, Associate Professor Graham Gee told the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services:

There’s an innate capacity in us to heal. It’s all about establishing safety, security and trust, and having the opportunity to work with someone you trust and get support from. As long as we remain committed to our healing, be really true and honest with ourselves, and reach out for support, the healing does come. But often we need help, that’s the thing, and there’s no shame in reaching out and asking for help.14

The Board of Inquiry heard about the importance of relational experiences to healing, such as ‘warm’ interactions that acknowledge a victim-survivor’s experiences and to help create a safe space that is conducive to healing.15

Support networks, such as family and friends, can also be important to a victim-survivor’s healing. One victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry: ‘The support of my family and friends has been important, and I couldn’t have spoken up today without them’.16 A participant at the Board of Inquiry’s Healing Roundtable said that while child sexual abuse ‘is an interpersonal crime’, healing requires ‘interpersonal engagements. It’s a relational experience, it’s not a transactional experience’.17

The role of communities in healing

Communities are very important in supporting victim-survivors and secondary victims to heal.

Trauma and healing both happen in the context of social connections, making community connectedness critical to the process of healing from trauma.18 A participant at the Board of Inquiry’s Healing Roundtable spoke about the importance of communities acknowledging past wrongs:

[T]here’s a whole bunch of people you’re having an impact on just by validating their experiences, just by making sure they’re heard, just by connecting them to a whole community of people who want to restore what was lost in their experience.19

The participant went on to speak about communities’ collective duty to allow victim-survivors and their families to unburden themselves from their trauma:

because it’s not their burden to carry it’s everybody’s. And naming that and talking about that as often as possible … that’s what makes for healing. If someone is unburdened they’re less likely to be distressed …20

A further participant at the Healing Roundtable also spoke about this issue, saying:

[I]f … there isn’t that community or collective response around this, then the person that is left holding all this and having to deal with the impacts of abuse on their own is very much the survivor.21

Communities can come together in the face of institutional child sexual abuse to foster healing.22 The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse highlighted one example of this, in which the Ballarat community united to support victim-survivors, through the LOUD fence movement. This movement involved parishioners and community members tying ribbons to the fences of institutions where child sexual abuse had occurred to demonstrate their solidarity with victim-survivors.23 Maureen Hatcher, Founder, LOUD fence Inc, gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that LOUD fence was established because many people in the Ballarat community were ‘concerned that there was nothing we could do. We were hearing all these truths being spoken from these brave voices that spoke out, and there was nothing as a community we could do to let them know that we supported them’.24

Fiona Cornforth, inaugural head of the National Centre for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing Research at the Australian National University and former Chief Executive Officer of The Healing Foundation, told the Board of Inquiry about the role the community can play in supporting healing:

[W]e all in the community can make it right going forward ... [i]n terms of applying those things that have always kept us safe and well in culture; for example, looking out for each other and leaving no one behind.25

A participant at the Healing Roundtable told the Board of Inquiry there is a difference between ownership of historical harm and responsibility for historical harm.26 The participant explained that while current communities are not responsible for historical harm, they must take ownership for responding to the harm that has been caused by institutional failures.27

The role of inquiries in healing

Increasingly, royal commissions and inquiries are being established with a truth-telling focus, providing people who have experienced abuse or suffered damage or injury in particular settings with an opportunity to share their experiences. These inquiries are under-pinned by principles that value the sharing of these experiences, and they provide victim-survivors with an opportunity to heal. In the context of historical child sexual abuse within institutions, inquiries with a truth-telling focus can also provide an opportunity for victim-survivors to rebuild what can often be low levels of trust in institutions, and to re-engage with those institutions if they wish to do so.28

Dr Katie Wright, Associate Professor, Department of Social Inquiry, La Trobe University, provided evidence to the Board of Inquiry that ‘victim-survivors across the world have called for public inquiries to examine abuse within institutions [—] sexual abuse and other forms of abuses as well’.29 As Dr Wright explained:

[Inquiries] provide a record of what has happened in the past. They are a mechanism that enables for the truth to come out regarding behaviour and the experiences of people in the past, and, importantly, the ways in which institutions handled particular kinds of problems.30

However, while Dr Wright’s evidence indicated that inquiries can be an important way to support healing, she noted that people will respond to inquiries in their own way, and that inquiries may be re-traumatising for some victim-survivors.31

The Board of Inquiry also heard directly from victim-survivors about the importance of its work to their healing. One victim-survivor said the Board of Inquiry could be a voice for victim survivors.32 Another victim-survivor described how the Board of Inquiry made him feel that he had finally been listened to, and that he believed other victim-survivors would benefit from hearing about other people’s experiences.33

Another victim-survivor described how the Board of Inquiry had brought some victim-survivors back together, and they were no longer frightened to talk about their experiences.34

An individual who works with victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse within institutions told the Board of Inquiry that inquiries can prompt victim-survivors to disclose their experience of abuse in order to prevent future harm to other children.35

The role of institutions in healing

The Commission of Inquiry into the Tasmanian Government’s Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Settings called institutional betrayal ‘a particular form of harm’ related to abuse and defined it as the ‘failure of an institution to provide a safe environment for a victim-survivor, as well as an institution’s failure to act once a disclosure of abuse is made’.36

In cases of institutional child sexual abuse, institutions can play an important role in healing by acknowledging the institutional betrayal and the child sexual abuse that occurred, providing a meaningful apology and taking actions to protect other children from sexual abuse.37 Through these types of actions, institutions can also provide an opportunity for victim-survivors to reconnect with the institution, if they choose to.38 Participants at the Healing Roundtable told the Board of Inquiry that to support healing, institutional responses should engage victim-survivors in a way that makes them feel ‘seen and heard and … no longer invisible’.39

However, the Board of Inquiry heard that institutional responses to revelations about historical child sexual abuse are often poor, and miss opportunities to support healing and the rebuilding of trust.40

A participant at the Healing Roundtable told the Board of Inquiry:

I think it’s really tragic that most institutions continue to do what they’ve always done and not address [these histories of institutional betrayal], because it can be such an opportunity for healing. You know, responsibility and all that aside, [addressing these histories of institutional betrayal is] just a great opportunity for those that want to engage in that sort of process.41

Institutions can contribute to healing by accepting responsibility and being accountable for the historical harm for which they are responsible. The refusal of institutions to do so can have negative impacts on victim-survivors of institutional child sexual abuse.42 The Board of Inquiry heard directly from victim-survivors about how it was important to their healing for the Department of Education (Department) to be accountable for the extent of historical child sexual abuse in government schools, and to understand the magnitude of its impacts.43

The Board of Inquiry heard evidence from Dr Rob Gordon OAM, Clinical Psychologist and trauma expert, that for schools where child sexual abuse occurred, the Department and local governments all have a role to play in helping communities to heal.44

There is significant scope for institutions, including the Department, to play a proactive and meaningful role in supporting people to heal from historical child sexual abuse in government schools.

Ways of healing from historical child sexual abuse

Healing is a personal journey. The Board of Inquiry heard that people’s experiences and healing pathways are different.45 Bravehearts, an organisation that works with, and advocates for, victim-survivors of child sexual abuse, told the Board of Inquiry that ‘[h]ealing may be defined differently by individual victims and survivors and their needs may vary’.46 Victim-survivors also told the Board of Inquiry that each victim-survivor’s needs are unique to the individual.47

The Board of Inquiry heard from people who work with victim-survivors and secondary victims that there is a need for responses to be led by victim-survivors,48 to maximise choice49 and to promote ‘a sense of hope’.50

This section focuses on some of the strategies and supports the Board of Inquiry was told may be helpful for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse.

Healing for victim-survivors

For many people affected by trauma and abuse, the decision to share their experience can be ‘the first step to healing’.51 In one study examining healing for adult male victim-survivors of child sexual abuse, participants described healing as a process of moving away from the effects of the child sexual abuse towards a ‘a sense of freedom, belonging, and power’.52

The initial disclosure by victim-survivors of their experience of child sexual abuse, which may take place decades after the child sexual abuse occurred, can be an important step towards healing.53 A victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry that opening up and telling friends about their experience of child sexual abuse has helped them deal with its impacts and stop blaming themselves for what happened.54 While studies suggest that a range of factors support recovery, victim-survivors talking about their experience is a key part of the healing process.55 In noting this, the Board of Inquiry also acknowledges that for some victim-survivors, their first disclosure was a negative experience — and, in some cases, re-traumatising.

A number of victim-survivors said that therapeutic supports had played a significant role in helping them to heal. Some described positive experiences with psychologists. For example, a victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry that working with their psychologist to embrace their inner child has been very powerful:

[My psychologist] made me recognise that … I could get in touch with that nine-year-old. I had no one around me when I was being abused, and she taught me that I could be that person now … to hold [their] hand and to give [them] a cuddle and say, ‘everything is okay’ … And the best thing I can do in terms of my healing is to recognise that and be confident that [they’re] being supported.56

Other victim-survivors told the Board of Inquiry about different strategies and supports they have used to further their healing and recovery. One victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry that transcendental meditation has ‘saved my life’. They also believe that a wellness centre, where people can mediate and feel peace and serenity, would be helpful for victim-survivors.57

Another victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry about the benefits of a short-term residential retreat,58 while a secondary victim told the Board of Inquiry they would like rehabilitation and wellness centres to be available to support people to heal, with a focus on the effects of child sexual abuse.59

Participants in the Lived Experience Roundtable and the Healing Roundtable told the Board of Inquiry that peer support and connecting with people who have a shared understanding of the experience of historical child sexual abuse can support healing and provide a sense of hope.60

The Board of Inquiry also heard that some victim-survivors have been drawn to careers or volunteer work helping children, because they saw it as a way to heal from their own childhood experiences. One victim-survivor described their desire to work in a career in a profession helping children, and said: ‘looking back now, I wanted to protect others because I wasn’t protected’.61 Another victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry that coaching sport has been an important part of his healing process. He said: ‘I love coaching sport and I love seeing young people get something out of sport. Coaching kids and seeing them enjoy sport have been part of my healing process. It has been a saviour for me and has gotten me back into sport again’.62

While giving back in this way can be helpful, it can also bring with it feelings of sadness, anger or confusion. One victim-survivor said: ‘what upsets me the most is that when I go to work, I protect kids and no one protected us’.63

The Board of Inquiry also heard that reconnecting with the institution where the historical child sexual abuse occurred (such as a school) can be healing for some victim-survivors.64 The Board of Inquiry heard that in these circumstances, reconnection can be a ‘wonderful hope-filled journey’.65

A former student of Trinity Grammar School, who has spoken publicly about his experience of sexual abuse as a child at the school, shared his experience of reconnecting with the Trinity Grammar community and engaging with the school.66 While events at Trinity Grammar are not within the scope of this Board of Inquiry, the experience of this victim-survivor are informative for the inquiry’s work. He said: ‘I feel energised and positive that the school has changed and that I have contributed to the wellbeing of the school community. After a lot of pain, it’s now finally a community that I want to be a part of’.67

Victim-survivors and secondary victims may also need to feel a sense of justice. A victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry that apologies were over-rated and not meaningful for her, and that an investigation into child sexual abuse in government schools was needed, saying: ‘I just don’t want it to happen to anyone else. I don’t want a system that allows child abuse to continue’. When asked what would support her healing, she replied, simply: ‘justice’.68 This perspective was shared by another victim-survivor, who told the Board of Inquiry they wanted to bring their abuser to justice.69

Some victim-survivors felt that changes were needed to hold alleged perpetrators accountable. For example, one victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry that alleged perpetrators needed to be brought ‘out of the darkness’.70 Another victim-survivor said that punishments for alleged perpetrators were inadequate.71 A secondary victim told the Board of Inquiry that the ‘lack of accountability for the profound harm [alleged perpetrators] have caused is deeply devastating and continuously harms the victims’.72

As discussed above, the process of healing is different for everyone. Some victim-survivors who shared their stories with the Board of Inquiry did not feel they had any further healing to do. For others, their healing process is a very long road. The Board of Inquiry heard evidence from Professor Patrick O’Leary, Co-Lead of the Disrupting Violence Beacon and Director of the Violence Research and Prevention Program, Griffith University, that in cases of complex trauma, healing is an ongoing process that ‘is never fully complete’.73 Professor O’Leary explained that in other contexts, healing ‘is seen as a final thing and that people move [on] and never revisit the issue’.74

In relation to complex trauma, however, Professor O’Leary’s evidence was that ‘people can reach a very safe and healing space, but years later, something can trigger them … that may take them back to that trauma’.75

As one victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry:

[S]omeone might need to ask me in 10 years … what was helpful about this journey? And what wasn’t? Because the things I think are helpful now, I might look down and go, no, that wasn’t so good. And some things I think maybe weren’t going to be helpful I found and discovered, or have been brave enough to attempt … will be helpful.76

Healing for secondary victims

The need for healing extends beyond victim-survivors, to include their loved ones. Dr Joe Tucci, CEO, Australian Childhood Foundation, gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that secondary victims’ role in supporting victim-survivors’ healing is under-appreciated.77 Dr Tucci’s evidence suggested that secondary victims are offered very little support in their own right, ‘despite these people often being the most significant support for the victim-survivor’.78

The Board of Inquiry heard that for some secondary victims, the inquiry’s work represented the beginning of their own process of healing. In some cases, this was because they had only learned about their loved ones’ experience of child sexual abuse in recent years.79 In other cases, it was because they felt, for the first time, that they could share their own experience as a secondary victim, and their engagement with the Board of Inquiry had made them ‘feel a lot better’.80

One secondary victim told the Board of Inquiry that they had first learned of their spouse’s experience of historical child sexual abuse less than three years before.81 This disclosure helped them understand some of their spouse’s behaviours, which included being non-responsive for days at a time and being unable to hug children in their family.82

Another secondary victim said it took time to decide whether to share their own experience with the Board of Inquiry, but that they ultimately decided to share their story as a way to ‘offload’ some of what they have been carrying, and their worry about the future.83

The healing process for secondary victims is complex.84 Research suggests that healing and recovery for secondary victims is characterised by a ‘dependence on the healing of the primary victims’.85 The healing process for victim-survivors is often ongoing, and secondary victims’ experiences of healing may be similarly protracted.86 Further, their healing may be affected by their continuing role supporting their loved one.

A secondary victim told the Board of Inquiry about their need for ‘respite’ as they supported their spouse to heal from historical child sexual abuse. They shared their hope for a better future, saying: ‘Where to from now? For me and my family, I just hope onward and upward’.87

Victim-survivors told the Board of Inquiry about their fears of burdening loved ones with their trauma.88 However, a secondary victim responded directly to this point, saying:

But really you’re not burdening anybody. [Victim-survivors’ loved ones] need to know and if they’re asking, tell them, and just be genuine. You want to reach your full potential as much as your partner and your family need to reach their full potential as well.89

Healing for affected communities

Communities can also be affected by historical child sexual abuse. The Board of Inquiry heard that ‘[s]exual abuse has long-term community and individual impact’.90 A victim-survivor told the Board of Inquiry that healing both personally and as a community are critical.91 Another victim-survivor reflected: ‘that [Beaumaris] community, how do they cope? Because not everyone was bad’.92 Chapter 8, Enduring impacts of child sexual abuse(opens in a new window), explores the impacts of historical child sexual abuse on the community of Beaumaris and surrounding areas.

Ballarat is another example of a community deeply affected by historical child sexual abuse. John Crowley, former Principal of St Patrick’s College Ballarat, told the Board of Inquiry’s Healing Roundtable about engaging with victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse at the school, as well as some of their families, and realising that the impacts of the child sexual abuse were widespread. Mr Crowley told the Board of Inquiry: ‘in my view this was a situation where a community, a whole community was damaged, and that deep distrust and betrayal was not only embedded at the victim-survivor level, but through generational families and through the community’.93

Mr Crowley spoke about how he believed St Patrick’s College was able to help some victim-survivors move forward in their lives through its commitment to acknowledging its past openly and truthfully through action; and how the apology that the school made for the ‘deep hurt’ the child sexual abuse caused was ‘not only to the victims and survivors, it was to the broader community of Ballarat’. Mr Crowley told the Board of Inquiry that as part the school’s work to address its past failings, he and current school staff, and later board members, met regularly with victim-survivors and their supporters, as well as community members, to discuss the school’s actions, responses and apology. He said that this was important to demonstrate that the school was ‘in this … for the long run’.94

Bushfire recovery models provide an example of how communities can heal from collective trauma. Bruce Esplin AM, former Victorian Emergency Management Commissioner and former Chair of Regional Arts Victoria, gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that ‘resilience and recovery build from the ground up’.95 Mr Esplin believes that successful approaches to community healing and recovery are driven at a community level, and gave evidence about how engaging in creative activities can help individuals and communities heal from collective trauma.96 Mr Esplin shared examples of how communities have used this model — called creative recovery — to heal from the Black Saturday bushfires, including by coming together to create mosaics, and to build and learn to play instruments that community members then used in local musical performances.97

Healing responses must also be trauma-informed and shaped by engagement with victim-survivors, drawing on principles of co-design.98 If communities engage with those community members who have experienced historical child sexual abuse about the responses they need, this will help victim-survivors recognise that they have a voice, and will support them to feel empowered and safe within their community.99

Finding a way forward

The Board of Inquiry understands that healing is not a uniform process. As one victim-survivor noted: ‘it’s an individual journey’.100

While no single action or approach will help all victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools to heal, support services and specific healing responses can play an important role in the process.

The evidence before the Board of Inquiry strongly suggests that there are some critical actions that can contribute to the healing process. These include:

- providing opportunities for recognition and acknowledgement of, and reflection on, historical child sexual abuse in government schools, its impacts and the strength of victim-survivors

- ensuring people have safe spaces to share their experiences

- ensuring the Department and Victorian Government demonstrate strong accountability for historical child sexual abuse, including being transparent about what happened, what government will do in response and how government will continue to work to protect children in school settings going forward

- providing support services that can contribute to victim-survivors’ healing.

What victim-survivors need from support services, including the challenges they face in having these needs met, is explored in detail in the chapters that follow. Chapter 16, Where people can go for support(opens in a new window), sets out what is available to victim-survivors. Chapter 17, Support needs and challenges(opens in a new window), explores the effectiveness of support services for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools.

Recommendations about specific ways to contribute to healing are then discussed in Chapter 18(opens in a new window).

Chapter 15 Endnotes

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3(d).

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Judy A Glaister, ‘Healing: Analysis of the Concept’ (2001) 7(2) International Journal of Nursing Practice 63, 64.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, 2008 Social Justice Report (Report 1, 2009) 158.

- Gregory Phillips, ‘Healing and Public Policy’ in Jon Altman and Melinda Hinkson (eds), Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia (Arena Publications Association, 2007) 141, 149.

- Kimberly Firth et al, ‘Healing, a Concept Analysis’ (2015) 4(6) Global Advances in Health and Medicine 44, 44.

- Kimberly Firth et al, ‘Healing, a Concept Analysis’ (2015) 4(6) Global Advances in Health and Medicine 44, 44.

- Kimberly Firth et al, ‘Healing, a Concept Analysis’ (2015) 4(6) Global Advances in Health and Medicine 44, 44.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, 2008 Social Justice Report (Report 1, 2009) 153.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, 2008 Social Justice Report (Report 1, 2009) 188.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, 2008 Social Justice Report (Report 1, 2009) 188.

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, Balit Durn Durn: Strong Brain, Mind, Intellect and Sense of Self (Report, August 2020) 12.

- Department of Health and Human Services (Vic), Balit Murrup: Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Framework 2017–2027 (Policy, 2017) 32.

- Personal communication from Graham Gee, Registered Psychologist, Victorian Aboriginal Health Service, to Department of Health and Human Services (Vic), 1 March 2017, cited in Department of Health and Human Services (Vic), Balit Murrup: Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Framework 2017–2027 (Policy, 2017) 32.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Transcript of ‘Bernard’, 24 October 2023, P-35 [10]–[13].

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Katie Schultz et al, ‘Key Roles of Community Connectedness in Healing from Trauma’ (2016) 6(1) Psychology of Violence 42, 42.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, December 2017) vol 3, 224.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, December 2017) vol 3, 227.

- Transcript of Maureen Hatcher, 24 November 2023, P-296 [27]–[30].

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Jonathan Tjandra, ‘From Fact Finding to Truth-Telling: An Analysis of the Changing Functions of Commonwealth Royal Commissions’ (2022) 45(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 341, 341–2.

- Transcript of Katie Wright, 24 October 2023, P-49 [7]–[9].

- Transcript of Katie Wright, 24 October 2023, P-49 [11]–[14].

- Transcript of Katie Wright, 24 October 2023, P-49 [35]–[39].

- Private session 3.

- Private session 14.

- Private session 33.

- Submission 17, 2.

- Commission of Inquiry into the Tasmanian Government’s Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Settings (Report, August 2023) vol 1, 50.

- Hazel Blunden et al, ‘Victims/Survivors’ Perceptions of Helpful Institutional Responses to Incidents of Institutional Child Sexual Abuse’ (2021) 30(1) Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 56, 64.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Family and Community Development Committee, Parliament of Victoria, Betrayal of Trust: Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Non-Government Organisations (Report, November 2013) vol 1, xlix.

- See e.g.: Private session 20; Private session 24; Private session 9.

- Statement of Rob Gordon, 22 November 2023, 15–16 [64].

- Private session 6; Private session 14.

- Submission 29, Bravehearts, 5.

- Private session 9; Private session 14.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Care Leavers of Australia Network, Submission No 22 to Senate Community Affairs References Committee, Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care (July 2003) 24.

- Claire Burke Draucker and Kathleen Petrovic, ‘Healing of Adult Male Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse’ (1996) 28(4) Journal of Nursing Scholarship 325, 326.

- Scott D Easton et al, ‘“From That Moment on My Life Changed”: Turning Points in the Healing Process for Men Recovering from Child Sexual Abuse’ (2015) 24(2) Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 152, 168.

- Private session 31.

- Maryam Kia-Keating, Lynn Sorsoli and Frances K Grossman, ‘Relational Challenges and Recovery Processes in Male Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse’ (2010) 25(4) Journal of Interpersonal Violence 666, 667; Kim M Anderson and Catherine Hiersteiner, ‘Recovering from Childhood Sexual Abuse: Is a “Storybook Ending” Possible?’ (2008) 36(5) American Journal of Family Therapy 413, 422; Brittany J Arias and Chad V Johnson, ‘Voices of Healing and Recovery from Childhood Sexual Abuse’ (2013) 22(7) Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 822, 836.

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Private session 2.

- Private session 6.

- Submission 21, 2.

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023; Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Private session 14.

- Statement of ‘Bernard’, 19 October 2023, 4 [32].

- Private session 20.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Submission 52.

- Submission 52, 3.

- Private session 3.

- Private session 22.

- Private session 2.

- Submission 4, 1.

- Submission 21, 1.

- Statement of Patrick O’Leary, 15 November 2023, 6 [40].

- Transcript of Patrick O’Leary, 16 November 2023, P-199 [46].

- Transcript of Patrick O’Leary, 16 November 2023, P-199 [47], P-200 [1]–[2].

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Statement of Joe Tucci, 21 November 2023, 14 [67].

- Statement of Joe Tucci, 21 November 2023, 14 [65].

- Private session 19.

- Private session 30.

- Private session 19.

- Private session 19.

- Private session 30.

- Rory Remer and Robert A Ferguson, ‘Becoming a Secondary Survivor of Sexual Assault’ (1995) 73(4) Journal of Counseling and Development 407, 408.

- Elaine Crabtree, Charlotte Wilson and Rosaleen McElvaney, ‘Childhood Sexual Abuse: Sibling Perspectives’ (2021) 36(5–6) Journal of Interpersonal Violence 3304, 3320.

- Rory Remer and Robert A Ferguson, ‘Becoming a Secondary Survivor of Sexual Assault’ (1995) 73(4) Journal of Counseling and Development 407, 411.

- Private session 30.

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Lived Experience Perspectives Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 1 December 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Transcript of Bruce Esplin, 24 November 2023, P-319 [38]–[39].

- Transcript of Bruce Esplin, 24 November 2023, P-312 [9]–[26], [42]–[43].

- Transcript of Bruce Esplin, 24 November 2023, P-315 [1]–[6].

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Healing Roundtable, Record of Proceedings, 29 November 2023.

- Private session 14.

Chapter 16

Where people can go for support

Introduction

Victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools often engage with several support services, rather than a single service, over the course of their lifetime.1 This is not surprising, given that child sexual abuse can have a range of impacts and those impacts can change over time.2

To understand the challenges victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools face when trying to access or use supports, it is helpful to explore the range of services available to them.

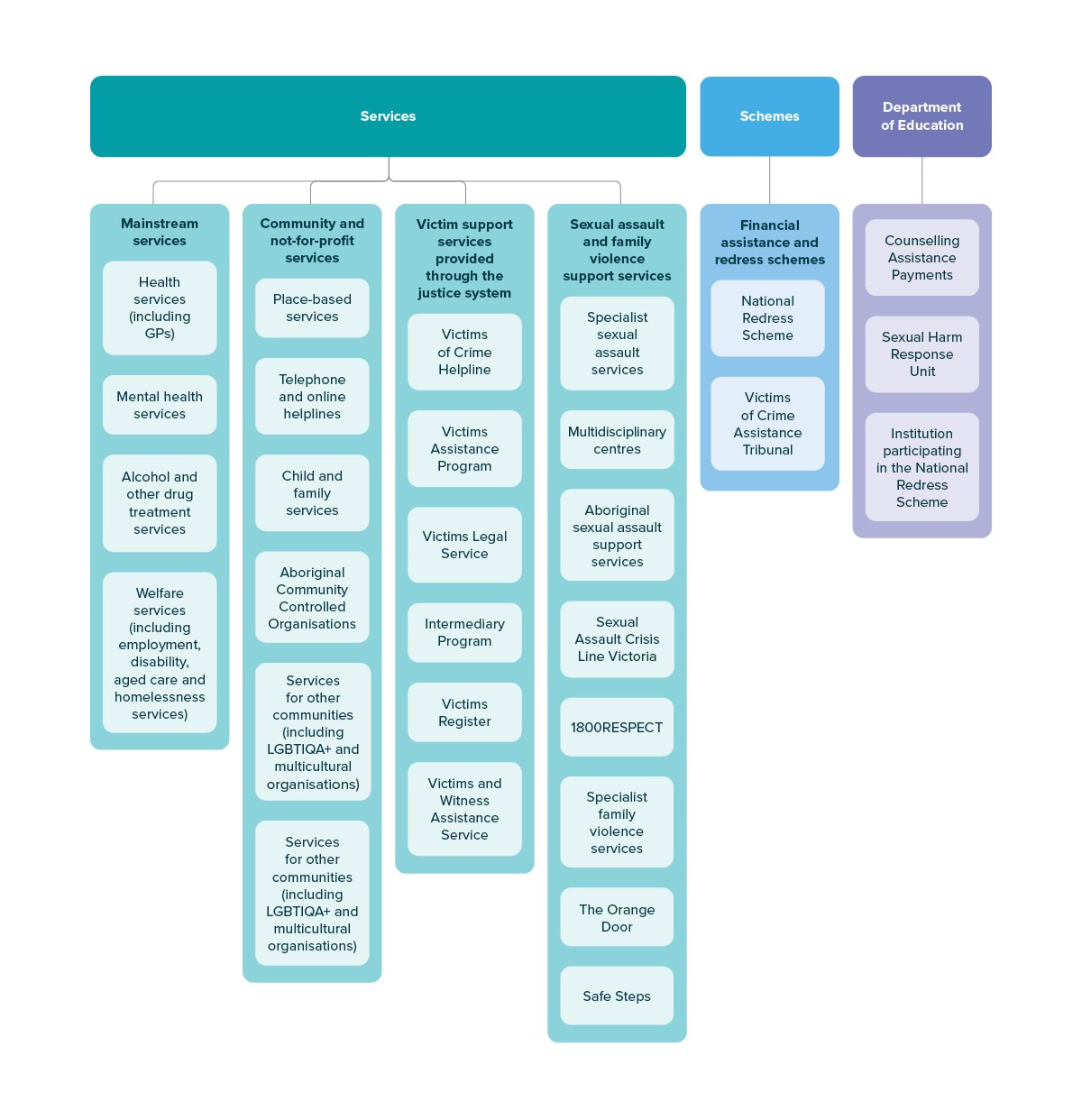

The service landscape for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools is complex. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Royal Commission) noted that the service response to victim-survivors of child sexual abuse, including historical child sexual abuse, comprises ‘a tangle of participants, professionals, services, settings and governance arrangements across various government portfolios’.3 The Board of Inquiry heard from a variety of sources that this continues to be the case and that there is no one ‘front door’ that victim-survivors can use to access support.

This Chapter outlines the types of services and schemes that victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools may engage with. This Chapter also outlines the supports available through the Department of Education (Department) for adults who were sexually abused in government schools.

Chapter 17, Support needs and challenges(opens in a new window), describes what the Board of Inquiry was told victim-survivors need from support services. It also considers the challenges that may prevent victim-survivors from having their needs met.

Support services accessed by victim-survivors

Under clause 3(e) of the Terms of Reference, the Board of Inquiry was asked to inquire into ‘whether there are effective support services for victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools’, having regard to ‘other inquiries and reforms that have taken place since the historical child sexual abuse occurred’.4

Victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools may seek different supports from a range of services over their life course. The victim-survivors who shared their experiences with the Board of Inquiry engaged with a wide range of different supports. For example, victim-survivors described engaging with GPs,5 psychologists,6 psychiatrists,7 lawyers,8 specialist sexual assault services,9 counsellors,10 alcohol and other drug treatment services,11 community organisations,12 and residential trauma and healing retreats.13

The Board of Inquiry has defined a ‘support service’ as a service that provides advocacy, support or therapeutic treatment to victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools. Informed by the Royal Commission, the Board of Inquiry has defined ‘advocacy’, ‘support’ and ‘therapeutic treatment’ as follows:

- advocacy — a wide range of activities to promote, protect and defend victim-survivors’ human rights and their rights to services and information. It may involve assisting victim-survivors to express their own needs, access information, understand their options and make informed decisions14

- support — emotional and practical assistance to victim-survivors to reduce their feelings of isolation, and promote connections and trusted relationships to aid in healing and recovery15

- therapeutic treatment — an overarching term covering a range of evidence-informed interventions that address the psychosocial impacts of child sexual abuse. Therapeutic treatments seek to improve victims’ physical, psychological and emotional wellbeing, and enhance quality of life.16

Support services can include:

- services providing responses to individuals who have experienced or been affected by historical child sexual abuse (including parents, partners, siblings and other secondary victims)

- services provided by government and non-government services (including publicly funded and private services)

- victim-survivor-led and peer-led services.

The Board of Inquiry acknowledges that some victim-survivors may require financial support, legal advice and assistance, social services support (for example, housing or Centrelink supports) or community support designed for specific cohorts. The Board of Inquiry’s Terms of Reference limited its ability to inquire into these types of support services in detail. However, where relevant the Board of Inquiry has referred to these supports and the important role that they can play for victim-survivors throughout Part D(opens in a new window).

Types of services

In Victoria, there are multiple services that victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse may access to meet their various needs (whether the child sexual abuse occurred in government schools or not). These services include the following:

- Mainstream services — These are universal services that are designed to be available to all Victorians. They include health services, mental health services, alcohol and other drug treatment services and welfare services.

- Community and not-for-profit services — These are offered by a wide range of non-government organisations and include place-based services (in specific regions), telephone and online helplines, and services for particular groups of people (for example, Aboriginal people). Many community organisations receive government funding to deliver services.

- Victim support services provided through the justice system — These services support victims of crime to access and move through legal processes, including criminal proceedings and seeking compensation through civil litigation.

- Sexual assault and family violence support services — These services offer crisis and therapeutic support, advocacy, practical assistance, and information and advice for people who have experienced any form of sexual assault (including child sexual abuse) or family violence.

These services are governed by a range of complex funding, service-delivery and regulatory arrangements. Many services are funded by either or both the Victorian and Commonwealth governments, with specific departments then being responsible for administering them. The administration of services includes allocating funding, and developing and managing service-delivery arrangements with organisations. Legislation or regulatory requirements often dictate how organisations deliver their services and acquit their obligations under their service agreements.17

Each service will deliver different types of support to victim-survivors. These may include advocacy, practical assistance navigating complex processes (such as legal proceedings or eligibility for compensation) and therapeutic support designed to support healing. Not all services deliver all forms of support, and their level of specialisation and intensiveness differs.

Victim-survivors may be engaged with multiple services at one time to meet their various needs.18 People may not identify as victim-survivors of child sexual abuse when accessing these services, even when engaging with the services to manage the impacts of the child sexual abuse they experienced.19

In some instances, victim-survivors may choose to pay to access a private service.

Diagram 8 provides an overview of where victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse may go to seek support. More information on a number of specific services is provided immediately below. Financial assistance and redress schemes, and support offered by the Department, are discussed later in this Chapter.

Mainstream services

While mainstream services are not designed specifically to respond to victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse, many victim-survivors and secondary victims engage with these services throughout their lives for assistance relating to the impacts of child sexual abuse.

Descriptions of some key mainstream services are given below.

Health services (including GPs)

Health services provide medical care and can be delivered in a range of settings, such as public and private hospitals,20 and primary and community health services.21

GPs provide primary healthcare, which is often the first point of contact a person has with health services.22 GPs can treat a range of health issues and can also refer people to a broader range of supports, including mental health services. The main way GPs facilitate access to mental health services is through developing mental health treatment plans for people, which allow them to access subsidised mental health treatment. Several victim-survivors and secondary victim survivors told the Board of Inquiry that they had consulted GPs about their mental health.23

Mental health services

Mental health services are provided by trained professionals in a range of settings, including through hospitals; residential, community and health services; and private and non-government organisations.

At present, victim-survivors may access up to 10 individual and 10 group sessions with certain mental health professionals (such as psychologists), subsidised under Medicare, with a mental health treatment plan developed by a GP.24 Because psychologists can set their own fees, Medicare may cover only some of the cost.25

In Victoria, victim-survivors who require more intensive support or who have complex mental health needs may receive mental health support from state-funded specialist mental health services, which may provide support in hospital settings or through community support services.26

Victoria is also rolling out new Mental Health and Wellbeing Locals (Locals), which provide treatment, care and support for people aged 26 years and over who are experiencing mental health concerns, including those with co-occurring alcohol and other drug treatment needs.27 The Locals provide a range of services — including therapies, wellbeing supports, education, peer support and self-help information — close to where people live and free of charge. A referral from a GP or other health professional is not required.28

Many victim-survivors who spoke to the Board of Inquiry had seen a mental health professional at some stage of their life, including through private practice and in hospitals.29

Alcohol and other drug treatment services

The Victorian Government funds a range of organisations to deliver alcohol and other drug treatment services through ‘treatment streams’. These treatment streams are counselling, withdrawal services (non-residential and residential), therapeutic day rehabilitation, residential rehabilitation, care and recovery coordination and pharmacotherapy. There are also population-specific services.30 Access to Victoria’s state-funded alcohol and other drug treatment system is generally free, though some services have a small cost.31

The Commonwealth Government also funds a National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline that provides ‘confidential support for people struggling with addiction’.32

Further, victim-survivors can pay for private alcohol and other drug treatment services, or engage with peer groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous.

Welfare services

‘Welfare services’ is an over-arching term referring to a wide range of services that ‘aim to encourage participation and independence and can help enhance a person’s wellbeing’.33 Welfare services are provided to people across a range of different ages and social and economic circumstances.

Examples of welfare services include:

- employment services to help people secure and maintain stable employment

- disability services to help people with disability and their carers participate in society

- aged care services to help older people with their living arrangements

- homelessness services to support people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness to access accommodation.34

Community and not-for-profit services

Community and not-for-profit organisations provide a range of services to the community. Some provide services in specific regions (place-based services), and some provide services to specific cohorts or communities, including children and families, Aboriginal people, LGBTIQA+ communities, and culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

The extent to which community organisations provide support that is suitable to meet the needs of victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse varies. Some provide broad wellbeing, counselling and information support that victim-survivors may access along with other members of the community. Others are funded by the Victorian or Commonwealth governments to provide services more tailored to victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse or victims of crime more broadly, such as support to make an application to the National Redress Scheme (discussed later in this Chapter).

Descriptions of some services provided by community and not-for-profit organisations are given below.

Telephone and online helplines

Victim-survivors can access a range of telephone and online helplines operated by not-for-profit organisations for advice and support.

While most of these are generalist mental health helplines, they can act as a gateway to other services and can offer advice about managing the mental health impacts of child sexual abuse. Telephone and online helplines include the following:

- Lifeline — This is a national charity providing crisis support and suicide prevention services via phone or online.35 Lifeline receives funding from the Commonwealth and Victorian governments, as well as other state and territory governments.36

- MensLine (delivered by Lifeline) — This is a free, nationwide service providing telephone and online counselling support for Australian men.37

- Suicide Call Back Service (delivered by Lifeline) — This is a free, nationwide service providing telephone and online counselling to people affected by suicide.38

- Beyond Blue — This is a not-for-profit organisation providing free telephone and online counselling.39 Beyond Blue receives funding from the Commonwealth and Victorian governments, as well as other state and territory governments.40

The above helplines all operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Services for Pre-1990 Care Leavers

Some community organisations are funded by the Commonwealth and Victorian governments to provide support to people who spent time in institutional or other forms of out-of-home care as children prior to 1990 — otherwise known as ‘Pre-1990 Care Leavers’ or ‘Forgotten Australians’.41 This includes services that provide advocacy, case management, referrals and counselling, as well as assistance to access people’s records and ward files.

For the purposes of the Board of Inquiry’s work, the definition of ‘government school’ in the Terms of Reference ‘excludes schools that were historically attached to orphanages or group homes’.42

Victim support services provided through the justice system

Victoria has several services for victims of crime and people engaging (or seeking to engage) in the justice system. Some of these services provide general support and referrals, while others are designed to support victims through specific processes, such as a criminal proceeding or seeking financial assistance.

Victims of Crime Helpline

The Department of Justice and Community Safety delivers a Victims of Crime Helpline, which is available between 8am and 11pm, seven days a week.43

The Victims of Crime Helpline offers free information, support and referrals for victims of reported and unreported crime.44 This can include information about victim entitlements, the criminal justice system and legal processes, and support to connect to other services.45 The Victims of Crime Helpline can also provide information and advice about reporting a crime, court processes and applying for financial assistance.46

The Victims of Crime Helpline also acts as a central intake point for the Victims Assistance Program (discussed below), referring eligible people who require more intensive support.47

The Department of Justice and Community Safety told the Board of Inquiry that the Victims of Crime Helpline receives:

- referrals from Victoria Police on behalf of victims of crime, where the crime involved physical or mental harm to a person (often referred to as ‘crimes against the person’)

- referrals from Victoria Police on behalf of male victim-survivors of family violence

- referrals from community organisations

- calls from victims of crime and the general public seeking information and support (self-referral).48

The Commonwealth Government provides funding to the Victims of Crime Helpline to provide family violence specialists as part of the service.49

Victims Assistance Program

The Department of Justice and Community Safety told the Board of Inquiry that the Victim Assistance Program (VAP), funded by the Victorian Government, provides flexible services that aim to meet the practical, emotional and psychological needs of victims of crime.50 The support that the VAP provides is tailored to the individual, and can include:

- assistance with day-to-day needs

- support to communicate with police

- organising counselling, transport and medical services

- assistance to get ready for court or prepare a Victim Impact Statement

- support to apply for financial assistance.51

The VAP is available to primary, secondary and/or related victims of crimes against the person perpetrated in Victoria.52 Crimes against the person include sexual assault (including historical child sexual abuse), family violence, physical assault and homicide.53

The VAP is delivered by a network of six community organisations.54 VAP workers are also co-located in 39 police stations across the state, in both metropolitan and regional locations.55

The Board of Inquiry was told that, in order to determine client eligibility, organisations undertake an assessment process to reasonably establish that a victim-survivor has been a victim of crime against the person. There is no requirement for the victim-survivor to have reported the crime to police.56

The VAP receives most of its referrals through the Victims of Crime Helpline and from other justice agencies, such as the Office of Public Prosecutions, although victim-survivors can also self-refer.57

Victims Legal Service

The Victorian Government funds the Victims Legal Service, which is delivered by Victoria Legal Aid, community legal centres and Aboriginal legal services.

The Victims Legal Service provides free legal advice and support to victim-survivors who need help to seek financial assistance through the Victims of Crime Assistance Tribunal or compensation from the person who committed the crime.58 The Victims Legal Service Helpline, run by Victoria Legal Aid, is the primary entry point into the service.59

The Department of Justice and Community Safety told the Board of Inquiry that the Commonwealth Government has funded a pilot program that will expand the Victims Legal Service to support victim-survivors to prevent their confidential communications and health information from being used in criminal proceedings, and to support Aboriginal women to report sexual offences to police.60 The program will run over a period of three years, until 2025–26.61

Other criminal justice services

Other services available for victim-survivors who have been involved in criminal proceedings include the following:

- Intermediary Program — This assists certain vulnerable witnesses to give evidence to the best of their ability through support from trained communication specialists, known as intermediaries.62 The program is available for eligible witnesses — children and young people aged under 18, and adults with a cognitive impairment — who are the complainants in sexual offence matters, or witnesses to homicide.63 The program is available in several court and police locations across Victoria.64

- Victims and Witness Assistance Service — Operated by the Office of Public Prosecutions, this service provides adult victims and witnesses with information about court processes, and support them to give evidence.65

- Victims Register — This provides information to eligible victims of crimes against the person (including sexual offences) about an offender’s sentence, including when the offender is due to be released from prison.66

Sexual assault and family violence support services

Sexual assault support services seek to address the impacts of sexual assault, including historical child sexual abuse, and provide a range of advocacy, support and therapeutic services.

Family violence services provide a range of supports for people experiencing family violence, including those who are in crisis and need immediate support.67 Previous research has demonstrated that women who have experienced child sexual abuse are more likely to experience family violence than other women,68 and thus may need support in this area.69

Specialist sexual assault services

Specialist sexual assault services are available across Victoria for people who have experienced recent or historical sexual assault (including historical child sexual abuse).70 These services are also available for non-offending family members and support people.71 Many of these services are called Centres Against Sexual Assault. Specialist sexual assault services are funded by the Victorian Government.72

Victoria’s specialist sexual assault services provide free and confidential services to people who have experienced sexual assault, including:

- counselling and advocacy for victim-survivors and others affected by sexual assault. Approaches can include psychoeducation, cognitive behavioural therapy and group therapies.73 They can also include eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing74

- assistance in managing the practical consequences of sexual assault (including support to access emergency housing or compensation), and support and information for non-offending family members and support people75

- brokerage funding, which is flexible funding that can be used to meet a victim-survivor’s basic material needs (including clothing and food), or to pay for services such as legal fees, and transport or childcare costs.76

Specialist sexual assault services also provide:

- immediate crisis response for people who have experienced a recent sexual assault, including crisis intervention, counselling, advocacy and liaison; for example, coordination of support and contact with child protection, police, and forensic and other medical personnel77

- support and services for children and young people exhibiting harmful sexual behaviours.78

In addition, specialist sexual assault services offer prevention activities, including community education, advocacy, and training and support for other professionals.79

Victim-survivors can self-refer to a specialist sexual assault service or may be referred to the service through a number of different agencies, including police.80

Multidisciplinary centres

Some specialist sexual assault services are located within multidisciplinary centres. Multidisciplinary centres co-locate a range of agencies in one building to provide a victim-centred response to sexual assault and child sexual abuse.81 Staff at multidisciplinary centres can include police, child protection staff, community health nurses and forensic medical officers.82 Some multidisciplinary centres also provide a response to family violence.83

Aboriginal sexual assault support services

The Victorian Government also funds four Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations to deliver ‘culturally safe support to Aboriginal Victorians who are victim-survivors of sexual violence or harm’.84

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH), provided evidence to the Board of Inquiry that these ‘cultural models of support … focus on safety, healing and wellbeing of Aboriginal people’.85 The DFFH evidence also indicates that ‘Aboriginal people who have experienced sexual violence and harm’ can self-refer or may be directed to this support from other programs within the same Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation.86

Sexual Assault Crisis Line

The Sexual Assault Crisis Line is Victoria’s statewide, after-hours telephone line providing crisis counselling support, information, advocacy and referrals to anyone living in Victoria who has experienced past or recent sexual assault.87 The Sexual Assault Crisis Line is also the central after-hours coordination centre for all recent sexual assaults.88

The Sexual Assault Crisis Line operates between 5pm weeknights through to 9am the next day, and across weekends and public holidays. Calls outside of those hours are directed to the relevant specialist sexual assault service.89

The Sexual Assault Crisis Line is funded by the Victorian Government.

1800RESPECT

1800RESPECT is a national information, counselling and support service for people affected by domestic, family or sexual violence. 1800RESPECT is a confidential service, and operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week.90

1800RESPECT can provide information on domestic, family and sexual violence, as well as phone counselling and referrals to other agencies.91

1800RESPECT is funded by the Commonwealth Government.92

Family violence support services

The Victorian Government also funds family violence support services, including the following:

- Specialist family violence services — These services are available across Victoria and provide a range of supports for victim-survivors of family violence. These can include case management activities, family violence risk assessment and management processes, safety planning, counselling and advocacy. Victim-survivors can self-refer to these services or they can be referred from an intake point such as The Orange Door or Safe Steps.93

- The Orange Door — The Orange Doors are located throughout Victoria and act as entry points into a range of services that victim-survivors may need.94 Services available at The Orange Doors are directed to victim-survivors of family violence and families needing extra support to care for children, and include risk and needs assessment, safety planning and crisis support.95

- Safe Steps — Safe Steps is Victoria’s 24/7 family violence response centre.96 It is staffed by family violence crisis specialists and provides victim-survivors with a range of supports.97

Redress and financial assistance schemes

Victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse (and other forms of sexual assault) may be able to seek redress or access financial assistance. Two schemes that victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse may engage with are the:

- National Redress Scheme

- Victims of Crime Assistance Tribunal (VOCAT).

Some of the services previously mentioned are involved in supporting victim-survivors engaging with these schemes.

National Redress Scheme

The National Redress Scheme was established by the Commonwealth Government in 2018 in response to recommendations made by the Royal Commission. The National Redress Scheme provides support to people who have experienced institutional child sexual abuse through three components:

- a monetary payment of up to $150,000

- a ‘Direct Personal Response’ (DPR) from the responsible institution or institutions under the DPR Program

- therapeutic support through the Counselling and Psychological Care Service (CPC Service).98

Victim-survivors can receive support before or during the application process, or as an element of redress. Table 5 summarises the primary supports victim-survivors can receive through the National Redress Scheme.

Table 5 Support through the national redress scheme

| Type of support | Description |

|---|---|

| Redress Support Services | The Commonwealth Government funds Redress Support Services across the country. Redress Support Services provide free, practical and emotional support to those making, or considering making, an application for redress.99 This can include referrals to knowmore for free legal advice and assistance, as well as to other community services.100 There are nine Redress Support Service providers in Victoria, and additional Redress Support Service providers that operate nationally.101 The Victorian Government also contributes funding to some of the Redress Support Services operating in Victoria, including the CPC Service and services for Pre-1990 Care Leavers. |

| Legal advice and assistance | The Commonwealth Government funds knowmore, a national legal service that provides free legal support for people considering applying for redress under the National Redress Scheme. knowmore can provide advice on how accepting an offer of redress may affect any future claims a victim-survivor may make.102 |

| Counselling and Psychological Care Service | Victim-survivors who receive an offer of redress are eligible to receive support through the CPC Service. The DFFH administers the CPC Service on behalf of all participating Victorian institutions.103 People who are family, extended family or close friends of, or have a family-like relationship with, a victim-survivor can also receive assistance under the CPC Service.104 The DFFH provides intake, assessment and navigation to services based on a person’s request.105 Counselling and psychological care provided under the CPC Service are delivered by practitioners in private and non-government organisations. Support that victim-survivors can access includes:

|

| Direct Personal Response Program | The DFFH leads the Victorian Government’s DPR Program. The DPR Program aims to provide recipients of redress with an opportunity to engage with the institution or institutions responsible for the child sexual abuse they experienced. This engagement ‘can include sharing experiences of the abuse and its impacts, institutional acknowledgement, apology, and demonstration of accountability for the child sexual abuse, and an opportunity to hear what the institution is doing to prevent and improve responses to child sexual abuse’.107 A DPR can be delivered face-to-face, as a written response, or by any other agreed method.108 While the DPR Program is not a therapeutic service, it can support people’s healing. |

Victims of Crime Assistance Tribunal

Victims of violent crime, including sexual offences, may apply to VOCAT for financial assistance related to expenses actually incurred, or reasonably likely to be incurred, as a direct result of the crime. This includes financial assistance to access counselling and psychological treatment services.109

People eligible to apply to VOCAT are ‘primary victims’ (persons injured as a result of a violent crime), ‘secondary victims’ (persons injured as a result of being present at or witnessing the violent crime) and ‘related victims’ (family members, dependants or intimate partners of a primary victim who died as a result of the violent crime).110

The Victims Legal Service is available to assist victim-survivors seeking to make an application to VOCAT.

VOCAT is being replaced by a new Victims of Crime Financial Assistance Scheme, which is expected to commence in 2024.111

The Department

The Department does not provide services directly to victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse in government schools. However, it does support victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse by:

- providing reimbursement for counselling and psychological services through Counselling Assistance Payments (as discussed further below)112

- providing information and advice to victim-survivors who have reported historical child sexual abuse to it (as discussed further below).113 It has recently established a Sexual Harm Response Unit that receives these reports114

- being a ‘participating State institution’ under the National Redress Scheme. State institutions that participate in this Scheme will be liable for providing redress to a person eligible for redress.115

Counselling Assistance Payments

The Board of Inquiry heard evidence from the Department that current and former students who have been sexually abused at a Victorian government school are able to receive limited financial assistance from the Department for counselling through Counselling Assistance Payments.116 Counselling Assistance Payments were established in 2006, prior to the introduction of the National Redress Scheme in 2018.117