Overview

This Board of Inquiry has endeavoured to conduct itself based on the principles of truth-telling. Central to this undertaking has been creating space to listen to, and understand, the experiences of victim-survivors and secondary victims.

Truth-telling is a process that allows individuals to come together to openly talk about historical wrongs and failures. It involves identifying and acknowledging past failures, understanding who was responsible for these failures, and ensuring they do not occur again.

Under clause 3(c) of its Terms of Reference, the Board of Inquiry was required to examine the response of the Department of Education (Department) to the experiences of victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse perpetrated by relevant employees at Beaumaris Primary School in the 1960s and 1970s, and by those relevant employees at certain other government schools between 1960 and December 1999. The Department’s response includes the Department ‘and its officers’ state of knowledge and any actions it took or failed to take at or around the time of the abuse’.1

The Department is responsible for the safety and welfare of students in Victorian government schools. The Board of Inquiry has found that the Department repeatedly failed to protect children from sexual abuse between 1960 and 1999.

This Part has five chapters:

- Chapter 10, The education system(opens in a new window), outlines the policy settings, legislative framework and sociocultural factors relevant to child safety in Victorian government schools between the 1960s and 1990s.

- Chapter 11, The alleged perpetrators(opens in a new window), documents matters relevant to allegations of historical child sexual abuse by relevant employees at Beaumaris Primary School and certain other government schools. It includes case studies on the alleged perpetrators, including their employment and criminal records, the allegations of child sexual abuse, and the Department’s knowledge and response to the child sexual abuse.

- Chapter 12, Grooming and disclosure(opens in a new window), examines how the experiences of victim-survivors describe features of grooming and manipulation, both of individuals and communities. It also explores barriers to disclosure of child sexual abuse at the relevant time, and how the Department’s conduct caused or contributed to those barriers.

- Chapter 13, System failings(opens in a new window), sets out the Board of Inquiry’s findings on the Department’s response to the allegations of child sexual abuse at the time, including analysis of the Department’s actions, or inaction, and missed opportunities to intervene.

- Chapter 14, Learning and improving(opens in a new window), provides a look ahead at learnings and improvements to prevent future child sexual abuse, including a brief analysis of changes over time and contemporary child safety practices.

The Board of Inquiry’s focus on allegations against specific persons at particular schools was determined by its Terms of Reference. As set out in Chapter 3, Scope and interpretation(opens in a new window), they required the Board of Inquiry to inquire into the experiences of victim-survivors of historical child sexual abuse who were sexually abused at Beaumaris Primary School by a teacher, school employee or contractor during the 1960s and 1970s (a ‘relevant employee’), and by those relevant employees at certain other Victorian government schools between 1960 and 1999. The Terms of Reference did not permit the Board of Inquiry to inquire into, for example, experiences of child sexual abuse by a teacher at a Victorian government school where the allegation was not made against a relevant employee. As a result, if an allegation was made against a teacher who did not teach at Beaumaris Primary School in the 1960s or 1970s, the Board of Inquiry could not inquire into that allegation. Throughout this Part, therefore, there is an emphasis on Beaumaris Primary School.

Notes to readers

Experiences of victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members

Throughout this report, the Board of Inquiry shares information that reflects some of the experiences that victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members shared with the Board of Inquiry.

The Board of Inquiry is deeply grateful to the victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members who so courageously shared their experiences of child sexual abuse. The Board of Inquiry also acknowledges those victim-survivors who have chosen not to disclose their experiences of child sexual abuse, and may never do so, including those who are no longer with us.

The Board of Inquiry asked people who engaged with it how they wanted their information to be managed. Some wished to share their experiences publicly. Some wished to do so anonymously and others wished to do so confidentially. Where people shared their experiences anonymously, the Board of Inquiry has not included any identifying information in this report. Where people shared their experiences confidentially, the Board of Inquiry used this information to inform its work, but has not included it in this report.

In relation to those who wished to share their experiences publicly, in some cases the Board of Inquiry determined that it should anonymise the information they shared. This decision was made for legal or related reasons, including in order to avoid causing prejudice to any current or future criminal or civil proceedings.

The Board of Inquiry shares the experiences of victim-survivors, secondary victims and affected community members to create an important public record of their recollections. However, the Board of Inquiry has not examined or tested these accounts for accuracy or weighed whether there is enough evidence to support criminal or civil proceedings. The approach the Board of Inquiry has taken in this regard is consistent with its objectives and its Terms of Reference.2

The Board of Inquiry expresses its immense gratitude to all who contributed, in any way, to its work. Those who shared their experiences have shaped the Board of Inquiry’s general findings and recommendations, and contributed to a shared understanding, among all Victorians, of the impact of child sexual abuse. The Board of Inquiry expects this report will reinforce the community’s commitment to better protect children from sexual abuse into the future.

Relevant employees

In the Terms of Reference, ‘relevant employee’ is defined to mean ‘a teacher or other government school employee or contractor who sexually abused a student at Beaumaris Primary School during the 1960s or 1970s’.3 The Board of Inquiry’s work has confirmed that several of these relevant employees have been convicted of multiple offences, including indecent assault and other offences against children. However, for various reasons, most of the experiences of child sexual abuse shared with the Board of Inquiry did not result (or have not yet resulted) in a criminal conviction. Accordingly, this Part refers to ‘alleged perpetrators’.

While the Board of Inquiry recognises that some of these alleged perpetrators have been convicted of offences and their child sexual abuse in relation to these offences is no longer ‘alleged’, in order to treat all experiences shared with the Board of Inquiry in the same way, and to avoid causing prejudice to any current or future criminal or civil proceedings, this Part still refers to them as ‘alleged perpetrators’. In doing so, the Board of Inquiry does not intend to devalue or minimise any of the experiences shared by victim-survivors, secondary victims or affected community members.

As set out in Chapter 3, Scope and interpretation(opens in a new window), six individuals have been identified by the Board of Inquiry as relevant employees. Four of the six relevant employees are discussed in detail in this Part. This is because more information and evidence was available to the Board of Inquiry in regard to these four relevant employees. This is no way diminishes the experiences of victim-survivors who were allegedly sexually abused as children by the two relevant employees who are not discussed in this Part.

Overview Endnotes

- Order in Council, ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3(c).

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023.

- Order in Council (Vic), ‘Appointment of a Board of Inquiry into Historical Child Sexual Abuse in Beaumaris Primary School and Certain Other Government Schools’, Victorian Government Gazette, No S 339, 28 June 2023, cl 3.3.

Chapter 10

The education system

Introduction

To examine how the Victorian education system responded to allegations of child sexual abuse at Beaumaris Primary School and certain other government schools, it is important to understand how the education system operated and was structured between 1960 and 1999.

This Chapter provides an overview of the education system and its administrative arrangements from the 1960s to the 1990s, as well as the roles and responsibilities of key bodies and office-holders in responding to allegations of child sexual abuse.

It also outlines the legislative and policy settings in place at the time to prevent and respond to child sexual abuse, including where no policies or procedures appear to have existed at all.

This Chapter concludes by exploring the organisational culture regarding child safety within the education system, and the informal practices that the system used as part of this culture in response to allegations of child sexual abuse.

Education system structure and responsibilities

In this report, the ‘education system’ means any body or office-holder established under legislative authority with responsibility for educational oversight or service delivery of government schools in Victoria.

Since 1960, the education system has undergone many changes. Those changes have arisen for various reasons, including as a result of government policy or broader economic and social changes.

The Department of Education (Department), as we know it now, has had various titles since 1960. In this report, ‘Department’ is used as an umbrella term to refer to the different iterations of the body during this period.

Administrative arrangements in the 1960s and 1970s

In the 1960s and 1970s the education system comprised the following:

- The Minister for Education — The Minister and their office were responsible for establishing, extending, maintaining, classifying and discontinuing government schools.1

- The Director-General — The Director-General was the ‘head’ of the Department. They reported to the Minister for Education and were responsible for administering the Education Act 1958 (Vic).2 In administering the Act, the Director-General could assign powers and duties to employees of the Department ‘as he thinks fit’.3

- The Teachers Tribunal — The Tribunal sat alongside the Department and was responsible for determining teacher salaries, the number of teaching positions, and the appointment and promotion of permanent teachers.4 The Tribunal also had responsibility for deciding on disciplinary measures where a ‘teacher is charged with being careless or negligent’.5 It consisted of three members: a chairman, a representative of the Government of Victoria appointed by the Governor in Council, and a representative of the teaching service elected by teachers.6

- The Committees of Classifiers — There were three Committees, one for each of the primary schools division, the secondary schools division and the technical schools division.7 The Committees also sat alongside the Department. The Committee for the primary schools division consisted of a chairman, who was an independent person appointed by the Governor in Council, the Chief Inspector and a teacher.8 It was responsible for managing teacher transfers and promotions.9

- The Council of Public Education (known as the Teachers Registration Council from 1972) — The Council sat alongside the Department. All teachers were required to be registered in Victoria in order to teach.10 The Council was responsible for registering teachers.11

- District inspectors — The role of district inspectors was to examine and inspect the performance of schools annually,12 as well as to assess the performance of teachers.13

- Government schools — Government schools were responsible for administering education to students and developing and implementing local policies and practices. They were led by school principals or head teachers.

A School Committee (also called a School Council) existed for every government school. They prepared school policies, strategies and communications, and managed finances at the school level.14 School Committees or Councils consisted of eight to 10 members who were nominated and chosen at a meeting of parents, guardians and the school principal, every two years.15

Within these structures, responsibility and oversight were usually divided across three major educational divisions: primary schooling, secondary schooling and technical education.16

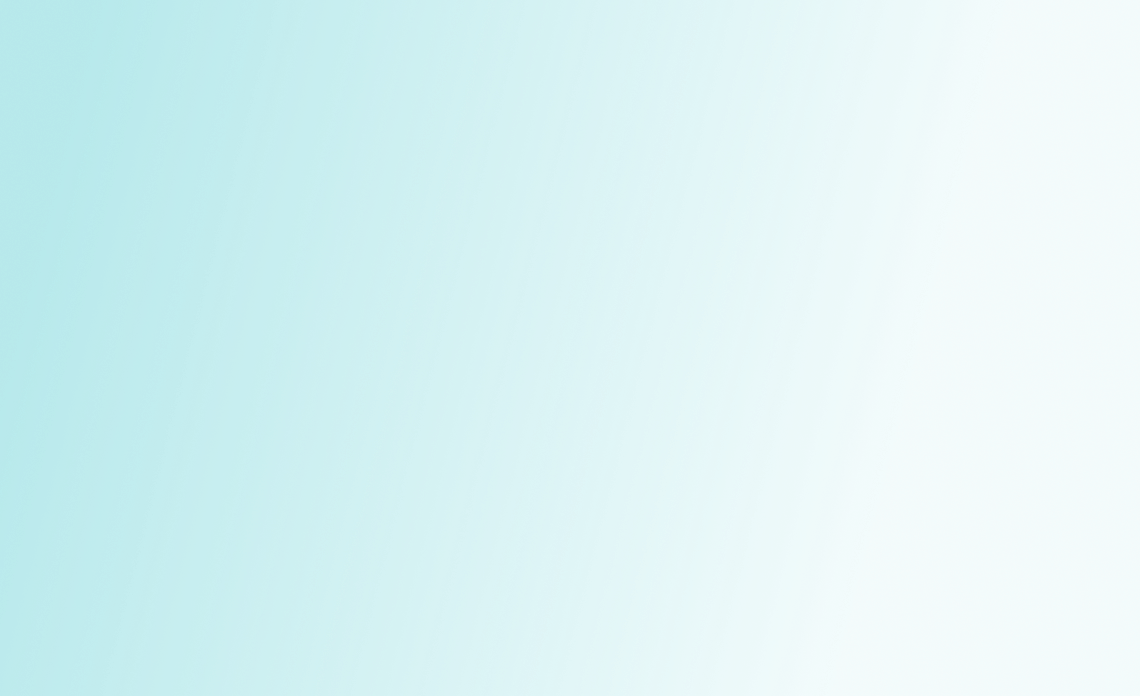

Diagram 6 provides a high-level visual representation of the structure of the education system during the 1960s and 1970s.

DIAGRAM 617

Legislative framework

The ‘legal framework’ refers to the legislation (also known as statutes or Acts) and regulations that set out the law as it relates to the education system. Together, they form the over-arching governance structure for the system. ‘Legislation’ refers to the laws passed by parliament18 that govern the development and delivery of education in Victoria. ‘Regulations’ are made under the authority of a statute and provide detail on how the law should be applied.19 This section considers the legal framework between 1960 and 1980.

Three pieces of legislation established the administrative structure of the education system, including roles, responsibilities and powers. These were the Education Act 1958 (Vic) (Education Act), the Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) (Teaching Service Act) and the Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) (Public Service Act).20

Regulations were passed in support of these two Acts. The Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) (Teaching Service Regulations 1958) were made under the Teaching Service Act and the Regulations General Instructions and Information 1962 (Vic) (Teaching Service Regulations 1962) were made under the Education Act.

Together, these Acts and regulations set out the legal framework for the employment, transfer and discipline of school-based staff. As outlined throughout this Chapter, references to managing teacher discipline were included in the Teaching Service Act (regarding breaches of that Act), the Teaching Service Regulations 1958 (regarding impaired moral behaviour) and the Public Service Act (regarding misconduct).21

The Board of Inquiry reviewed amendments to the legal framework between 1960 and 1980. It did not appear that the amendments in this period made any significant changes that would alter the accuracy of any of the legislative and regulatory descriptions between 1960 and 1980 outlined in this Chapter.

Roles and responsibilities for investigating and responding to child sexual abuse

A review of the relevant legislation, regulations and other material available to the Board of Inquiry did not clearly identify which specific bodies and office-holders within the education system were responsible for investigating and responding to allegations of child sexual abuse in schools in the 1960s and 1970s. This gap was confirmed by the evidence of Dr David Howes PSM, Deputy Secretary, Schools and Regional Services, Department of Education, who said: ‘As far as can be determined, there was no specific allocation of responsibility for managing and responding to allegations or incidents of child sexual abuse in the period 1 January 1960 to 31 December 1984’.22

The lack of a specific allocation of responsibility does not mean, however, that office-holders in the Department had no responsibility for managing and responding to child sexual abuse in government schools. In fact, the Board of Inquiry identified several offices and roles where the person exercising powers and discharging functions in accordance with that office or role could have dealt with allegations of child sexual abuse. These are discussed in turn below.

The Director-General

The Director-General was the Head of the Department, reported to the Minister for Education, and was responsible for administering the Education Act.23

The Director-General had responsibility for receiving reports about ‘any member under his control who is guilty of a breach’ of the Teaching Service Act (‘members’ included any employee of the Department, such as teachers, principals and district inspectors).24

Under the Public Service Act, the Director-General had responsibility for hearing and determining the disciplinary approach for any officer who was ‘guilty of any misconduct’.25 This included the power to reprimand, caution or impose a fine on an officer if they believed that the alleged offence was minor.26

The Director-General could also make a report to the Minister for Education, who could then refer the matter to the Teachers Tribunal for investigation and decision, or back to the Director-General for decision.27 Dr Howes gave evidence that the Director-General could also refer matters directly to district inspectors and the Teachers Tribunal for investigation.28 Dr Howes also gave evidence that in some instances, it appears that district inspectors could make decisions about how to manage allegations on behalf of the Department, without approval by the Director-General.29

When an allegation led to a charge of misconduct or was considered ‘to be of such a nature as to warrant the making of a report to the Minister’, the teacher could be suspended pending investigation outcomes.30

While the Director-General was accountable for the review of misconduct matters, the Board of Inquiry understands that they delegated their responsibilities for primary education to the Chief Inspector.31

The legislation and regulations did not refer to child sexual abuse in terms (nor define the term ‘misconduct’); however, the evidence of Dr Howes was that he believed that child sexual abuse would have fallen within the following clause in the Teaching Service Regulations 1958:

A member shall not engage even indirectly in any business which would have the effect of impairing his moral influence over his pupils or in the community generally, and he must not, even out of school hours, be guilty of any action unbecoming a person holding his position.32

School principals and teachers

School principals were responsible for the day-to-day running of their school and the implementation of policies at the school level. This included listening to and determining appropriate courses of action in response to reports of alleged misconduct.33

Under the Teaching Services Act and the Teaching Service Regulations 1958, principals and teachers with supervisory responsibilities were obliged to report breaches of misconduct to the Director-General.34

District inspectors

The evidence received by the Board of Inquiry, and other information considered by the Board of Inquiry, makes clear that as a matter of practice, the role of the district inspector was one of the most important within the Department with respect to the management of allegations of child sexual abuse.

The role of district inspector was established in 1851 and existed until 1983.35 Despite the fact that district inspectors were an entrenched feature of the school system in Victoria for so long, little has been written about them. In understanding the system of district inspectors and their work, the Board of Inquiry has relied principally on the research of former district inspector Mr David Holloway and of Ball, Cunningham and Radford, as well as personal accounts of former district inspectors provided by the Department.36

The first Education Act in Victoria, enacted in 1872, referenced the role of inspectors, of which district inspectors were a subset. The Education Act 1872 (Vic) specified that the Department shall consist of ‘a Minister … a Secretary, an Inspector-General, inspectors, teachers and such other officers as may be deemed necessary’.37

The Teaching Service Regulations 1962 articulated the role of inspectors, including that they ‘inspect and examine’ a school annually, and make as many additional visits as they considered necessary.38 During the annual examination, inspectors were instructed to examine a range of things, including all official records of the school, the ‘discipline and tone of the school’, and how the school ‘fills in the community’.39

The Board of Inquiry also received information from the Department that:

District Inspectors had formal Ministerial authority to ‘inspect any (government) school ... for the purpose of ascertaining whether the registers are being kept as required and whether efficient and regular instruction ... is being given[.]’ They held a similar authority to inspect non-government schools.40

District inspectors assessed teacher performance and provided grades on their performance, from ‘unsatisfactory’ to ‘outstanding’, which were used to inform the promotion of teachers.41

The Chief Inspector oversaw district inspectors. The Chief Inspector, in turn, was assisted by assistant chief inspectors.42

Outside of their advisory and assessment duties, district inspectors were in charge of fielding, investigating and responding to complaints and concerns regarding teachers.43 They could also be contacted by the police if a teacher was being investigated.44 The evidence of Dr Howes confirmed that the role of a district inspector included responding to allegations of child sexual abuse against a teacher.45 As a result, from the perspective of understanding how a complaint about sexual abuse of a student by a teacher might be handled during this period, the district inspector’s role is critical.

District inspectors were ultimately accountable to the Director-General and received instructions and advice from the Department.46 They were known to carry out their day-to-day work with minimal direct supervision, and would engage directly with schools and parents to manage complaints and propose courses of action.47

According to Ball, Cunningham and Radford, when ‘more serious complaints’ were made, district inspectors could be required to investigate the claim and make recommendations to the Director-General on the appropriate course of action.48 However, a former district inspector’s report (prepared in the context of a civil proceeding but relied upon by the Department before the Board of Inquiry) said that ‘the nature of a complaint would dictate the steps’ a district inspector would take.49 It is clear from the former district inspector’s report that if a district inspector did not consider the complaint to be serious, it could be dealt with informally.50

Although district inspectors were responsible for such investigations, assistant chief inspectors or the Chief Inspector could make ‘special inspections’ of their own where they deemed intervention was justified.51

While the role of district inspectors was described in the Teaching Service Regulations 1962, there were minimal policies to guide how they should acquit their functions.

As far back as 1882, a Royal Commission into the Administration, Organisation, and General Condition of the Existing System of Public Instruction found that district inspectors had been given no instructions to inquire into the ‘moral character’ of teachers.52 The Board of Inquiry understands that this continued to be the case right up until the officer of district inspector was abolished in 1983.

A 1961 Australian Council for Education Research study similarly found that although district inspectors’ responsibilities were set out in regulations, ‘[a] good deal of the detail of [their] duties [were] not put in printed form but [were] the result of tradition and practice transmitted by word of mouth’.53

There was some anecdotal information, however, that points to some form of informal understanding about how to handle allegations of child sexual abuse.

The former district inspector’s report noted that ‘[a]fter receiving a serious complaint, District Inspectors would notify the Department by reporting it to the responsible Director of Primary Education at Treasury Place’.54 He also said that if the complaint involved sexual abuse, he would have contacted Victoria Police and the Department.55 Whether other district inspectors shared this view or took a similar approach is unknown.

Information provided to the Department by another former district inspector described a ‘reference system’ for managing complaints.56 This district inspector noted that when a complaint was made to the Director-General, it was referred to as a ‘yellow’ notice and would be investigated by the relevant district inspector.57

The Teachers Tribunal

The Teachers Tribunal was responsible for a range of matters related to teacher employment and promotion.58 It was also responsible for hearing, inquiring into, and making decisions regarding charges made under the Teaching Service Act and the Public Service Act,59 including the Teaching Service Regulations 1958. As noted earlier, these regulations included a clause relating to a teacher not engaging in any behaviour that would ‘have the effect of impairing his moral influence over students’,60 and Dr Howes gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that he believed this clause would cover child sexual abuse.61

The Director-General was empowered to report a matter to the Tribunal if a teacher was ‘charged with being careless or negligent in the discharge of [their] duties or with being inefficient or incompetent’.62 Once a matter had been so referred, the Tribunal could ‘inquire into the truth of such charges …’.63 The Tribunal would require the teacher to state in writing whether they admitted to the charge.64 If the teacher denied the claims, the Tribunal would conduct an inquiry into the charge or refer the charge to a board of inquiry appointed to investigate and report back to the Tribunal.65

Under the Public Service Act, the Tribunal had powers to investigate and summon the provision of evidence.66 For example, this could include reviewing evidence placed before it, hearing from the teacher, and receiving character references and other materials for consideration.67

This Board of Inquiry could not find any policies or procedures that outlined how the Tribunal conducted its reviews.

If the charge was proven, the Tribunal (and from 1981 onwards, the Director-General) was responsible for deciding the disciplinary outcome for the teacher.68 This could include imposing a pecuniary penalty, reducing the teacher to a lower employment class, or dismissing the teacher from the teaching service.69

Structural changes across the 1980s and 1990s

In the 1980s, major structural changes were made to the education system in Victoria.

In 1980, the Victorian Government published a white paper that examined government schools and recommended new administrative arrangements, which reflected a move towards decentralisation.70 While the white paper had 59 pages dedicated to assessing the administration of the education system, there were no explicit references to complaint management processes or child safety practices.

In 1981, the Education Service Act 1981 (Vic) repealed the Teaching Service Act. The Teachers Tribunal was abolished and the Secretary of the Department (previously called the Director-General) became responsible for investigating and responding to allegations of misconduct against teachers, and a new Education Service Appeal Board was introduced to hear appeals against disciplinary action.71

In 1983, the Teaching Service Act 1983 (Vic) was passed by Parliament, establishing the Teaching Service Disciplinary Board as the body responsible for inquiring into and determining disciplinary matters in relation to the teaching service.72

The Department took on functions related to the appointments, transfers and promotions of teachers. In 2006, Merit Protection Boards were introduced to advise the Minister and Secretary ‘about principles of merit and equity to be applied in the teaching service’.73

The Department itself also underwent a restructure in the early 1980s. A new regional model was introduced, with regional directors overseeing clusters of schools.74 In 1983 the office of district inspector was abolished.75

In 1993 the Children and Young Persons Act 1989 (Vic) introduced mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse for particular professions, which applied to teachers from 1994.76 Mandatory reporting marked a fundamental shift in the way schools and the Department responded to and reported child sexual abuse.

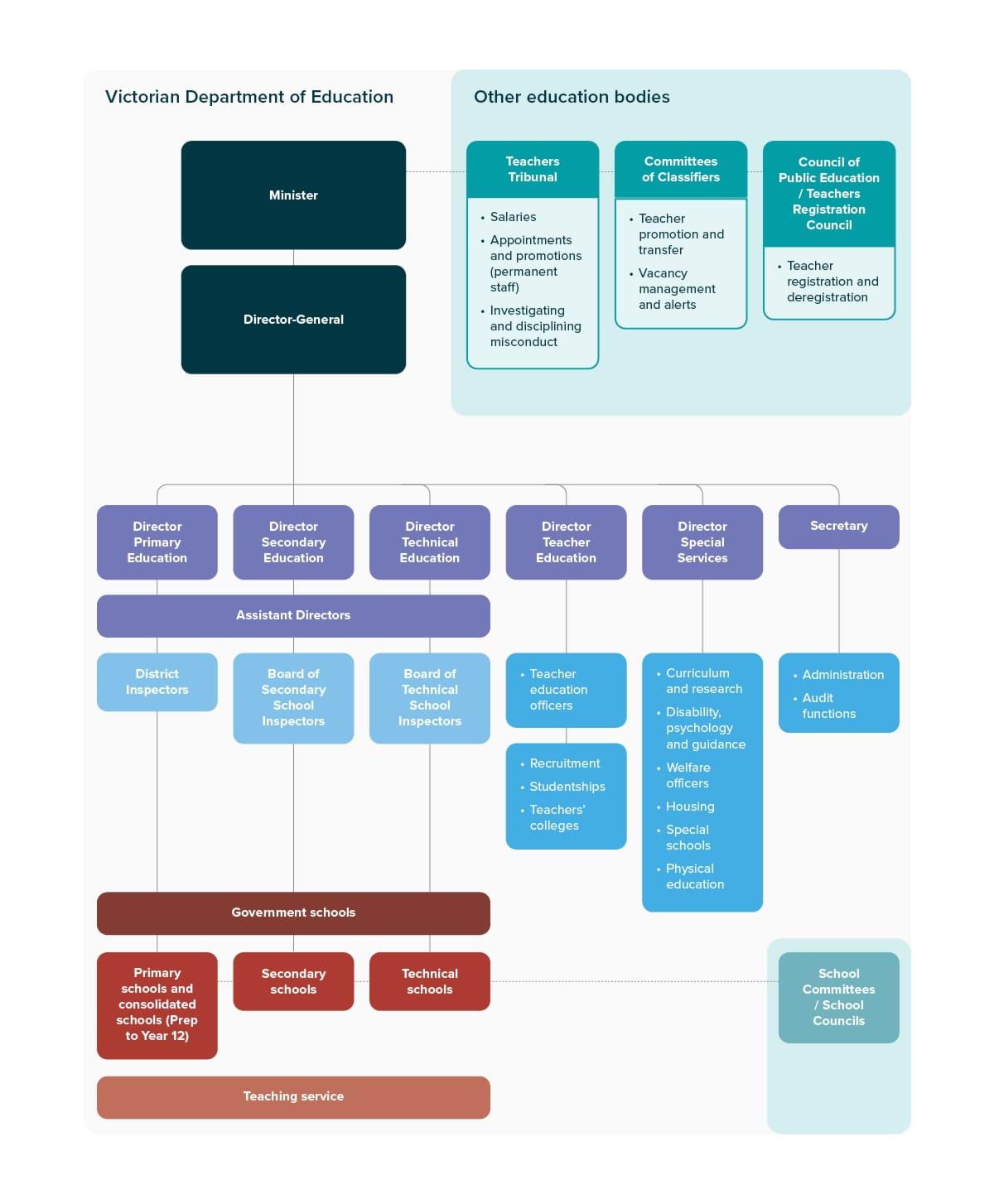

Diagram 7 provides a high-level overview of the education system structure in the 1980s and 1990s.

DIAGRAM 777

Historical child safety policies, procedures and practices in the education system

This section summarises policies, procedures and practices in government schools related to child safety, including child sexual abuse. The Board of Inquiry’s findings regarding the use of these mechanisms, their effectiveness and policy gaps are discussed in Chapter 13, System failings(opens in a new window).

Prevention policies

As explored in Chapter 13(opens in a new window), there is no evidence before the Board of Inquiry, or any other material, to suggest that any policies were in place in the period from 1960 to 1994 in the Victorian government school system concerning child sexual abuse in schools. In 1994 mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse was introduced for teachers, which was accompanied by several policies regarding preventing and responding to child sexual abuse.

This is consistent with the evidence of Professor Lisa Featherstone, Head of School, School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry, University of Queensland that there was minimal focus on child protection in schools during this period.78 This is explored further in Chapter 5, Children’s rights and safety in context(opens in a new window).

Investigation and reporting policies and procedures

Despite having a legislative and regulatory framework in place to respond to allegations of misconduct against teachers, the Department was unable to identify any policies or procedures in place between 1960 and 1994 that provided guidance on how to manage or respond to child sexual abuse in the education system. Dr Howes gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry as follows:

There simply were no policies or procedures that we have been able to find that would indicate how these allegations should be followed through.79

Dr Howes also confirmed the Department was unable to locate any policies or procedures enforcing adherence to the legal framework.80

The only policy the Department was able to locate that referred to misconduct with students was a memorandum issued by the Director-General in 1952 at the request of head teachers. The memorandum stated, ‘[f]rom time to time, the attention of the department is drawn to the dangers that men teachers incur through indiscreet and thoughtless actions with regard to girl pupils’.81 The memorandum advised male teachers ‘in their own interests, against any action liable to misinterpretation’, ‘never to place their hands on pupils’.82

A similar memorandum was circulated to head teachers in 1960, though the reference to placing hands on pupils was removed.83 The Board of Inquiry could not find any policies describing how schools should monitor or implement the memorandum, or what to do in the event of an incident.

There were also no documented policies outlining how complaints and allegations should be handled by principals, district inspectors or senior officials in the Department.

As discussed earlier, the role of inspectors (of which district inspectors were a subset) was set out in the Teaching Service Regulations 1962. The Board of Inquiry did not receive any information regarding the existence of policies guiding district inspectors on how to carry out their duties.

Jenny Atta PSM, Secretary, Department of Education, gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that there was a ‘sweep of significant change from the start of this century’ regarding policies and procedures for reporting child sexual abuse, in response to mandatory reporting.84 Ms Atta noted that the guidance for school principals, and later for the teaching service, was ‘significantly revamped’ to provide clear policies around responding to allegations of sexual abuse.85

These changes are discussed in detail in Chapter 14, Learning and improving(opens in a new window).

Record management policies and procedures

The Department was unable to locate any record management policies and procedures between 1960 and 1994 in relation to allegations or incidents of child sexual abuse in the Victorian education system.86 Ms Atta gave evidence that the inability of the Department to find this information indicated an absence of record-keeping policies in the past.87 Notably, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Royal Commission) also found that many schools had poor record-keeping and management procedures in place for complaints about child sexual abuse.88

Under Regulations and General Instructions and Information (1962), district inspectors were required to provide an official report for each school and teacher annually.89 The reports included performance information and could also cover developing trends and problems.90 It is not clear whether this included misconduct issues, such as allegations of child sexual abuse.

The Board of Inquiry’s analysis of some of these district inspector reports did not reveal any records of child sexual abuse allegations. It is noted, however, that material available to the Board of Inquiry included a record of an interview with a former district inspector in which the inspector said that ‘records such as complaints materials’ were ‘supposed to be destroyed after a certain number of years’.91 While the Board of Inquiry did not uncover any formal policy in relation to this, it is possible an informal policy or practice of this kind existed and would in part explain the absence of records of child sexual abuse allegations.

The Teachers Tribunal was also required to report annually to the Minister and Parliament.92 The Board of Inquiry reviewed several annual reports prepared by the Teachers Tribunal between 1960 and 1981 (when the Teachers Tribunal was abolished). These reports included high-level information on disciplinary actions against teachers determined by the Tribunal in a given year, including the number of determinations made and the number of disciplinary actions taken, by type.93 There was not sufficient detail recorded in the annual reports to understand why disciplinary action was taken in a given case. The Board of Inquiry was unable to find any information on the reporting policies that informed the annual reports, aside from legislative requirements.

In regard to the Teachers Tribunal’s communication and record-keeping, in 1973, the Victorian Teachers’ Union raised concerns that its method of communicating decisions was ‘ineffective’ and ‘inconceivable’, in that ‘decisions are not communicated or communicated tardily’.94

The Board of Inquiry notes that the Department issued a memorandum to schools in 1963 regarding the importance of record-keeping in relation to physical accidents by students that might occur at schools.95 However, two features of this memorandum are telling. First, its concern appears to be the need for accurate record-keeping in the event of a civil claim being brought against the Department.96 Second, there was no mention of child sexual abuse.

Training requirements for teachers

In the 1960s and 1970s, regulations required teachers and principals to report any ‘moral impairment’ of or ‘misconduct’ by teachers that breached the Teaching Service Act.97 Yet Ms Atta gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that during this time ‘there was no evidence of structured training of any kind that went to issues of understanding how to identify … sexual abuse [and] how to respond to [it] appropriately’.98

The Royal Commission found that, based on its inquiry from around the 1930s onwards, ‘even where school staff observed grooming behaviour, they did not immediately recognise its link to child sexual abuse’.99 The Royal Commission also found that the reasons for this included that staff received inadequate training and guidance.100

Employment and transfer policies and practices

Under the Teaching Service Act 1958, the Teachers Tribunal was responsible for appointing permanent teachers to the teaching service.101 This could only occur after transfers and promotions of teachers already in the teaching service had been considered by the relevant Committee of Classifiers.102

The Director-General could also transfer a teacher by certifying to the Minister that it was in the public interest or in the interest of efficiency that a teacher be transferred from one school to another.103

As noted earlier, the Board of Inquiry found that no policies concerning child sexual abuse existed between 1960 and 1994, in relation to teacher employment and transfer or otherwise.104

Notwithstanding the absence of policies, it is clear there was a longstanding practice in the Victorian education system of transferring teachers to other schools in response to allegations against them. The 1882 Royal Commission into the Administration, Organisation, and General Condition of the Existing System of Public Instruction noted that district inspectors who had received reports of ‘immoral conduct’ often recommended the teacher be moved to another school or different duties, rather than be dismissed altogether.105 In 1882, the Department noted that it was important to consider the issue from the teacher’s perspective, to reduce the risk of reputational damage for what it saw as a ‘comparatively small offence’, such as ‘undue familiarity with a female student’.106 The informal practice of transferring teachers is discussed further below.

Dr Howes gave evidence that, during the 1960s to the 1980s, the education system used transfers to uphold the reputation of teachers and considered that transfers were an appropriate disciplinary tool for child sexual abuse, rather than termination.107 This is discussed in detail in Chapter 13(opens in a new window).

The Department was also unable to find any policies or procedures related to vetting teachers during recruitment to mitigate risks of child sexual abuse between 1960 and the end of 1984.108

Information-sharing policies

Evidence provided by the Department to the Board of Inquiry established that there were no policies relating to how it liaised with other agencies and organisations responsible for investigating child sexual abuse, including Victoria Police, in the period from 1960 to 1994.109

Looking to information that might have been shared with the Department, based on a Police Standing Order in 1957 and police manuals in the 1990s, it appears that between 1960 and 1994 there was an obligation on Victoria Police to share crime reports with the Department regarding information that a student had been sexually abused while in the care of a government school.110

Informal practices and culture

The organisational culture within which official policies and procedures are operationalised also has an impact on ensuring the safety of children.111

Organisational culture refers to the shared values and beliefs that guide how people working in an organisation interact with one another and undertake their work. It manifests itself as behaviours, customs and practices.112

Unlike official policies and procedures, organisational culture is strongly influenced by covert messages, values and behaviours that flow through an organisation.113 These can significantly affect the rigour with which legal requirements, policies and procedures are implemented, as well as the behaviour of individuals.114

The impacts of organisational culture can be hard to measure and are rarely documented or recorded. The Royal Commission found that cultural factors within institutions, including government schools, played a significant role in how institutions considered and responded to suspicions, allegations and instances of child sexual abuse.115

Broad factors influencing education system culture

A range of factors influenced the culture of the education system in the 1960s and 1970s with respect to child sexual abuse, including the following:

- Sociocultural beliefs and understandings — There was a lack of understanding of or knowledge about child sexual abuse and grooming, a perception that children were to be compliant, and a tendency not to believe children who disclosed sexual abuse (discussed in Chapter 12, Grooming and disclosure(opens in a new window)).116

- Legislative, regulatory and policy settings — Relatively few safeguards were in place to protect children’s safety and wellbeing, especially from child sexual abuse, and there was little focus on or understanding of children’s rights (discussed in Chapter 6, Time and place(opens in a new window)).117

In addition, the economic and social settings underpinning education policy at the time likely had an impact on the education system’s culture.

Victoria’s population grew rapidly during the 1960s and 1970s, increasing from 2.9 million in 1960 to 3.9 million by 1980.118 This was due to service personnel returning after the Second World War and starting families, and immigration.119 A 1969 report of the Committee on State Education in Victoria noted that enrolments in secondary and technical schools had risen from 57,037 in 1952 to 185,000 in 1966, an increase of 229 per cent.120

In response, district inspectors increasingly devoted their time to advising the Department on proposals for new schools.121 School principals began adopting more of a monitoring role in relation to performance and issues, while district inspectors took up advisory functions.122 A 1960 report of the Committee on State Education in Victoria, found that district inspectors could not properly carry out their functions due to the pressure of administrative duties.123 The report also found that there were challenges with recruiting district inspectors with the right skills and qualities.124

At the same time, the funding approach to government schools and non-government schools was being debated at the federal and state levels, with federal funding for government schools only starting to flow from the mid-1960s.125 This meant schools were heavily focused on resource management. In addition, teachers were well protected by their unions, which also raised concerns with the way teacher discipline and promotions were managed through existing governance structures.126

It was difficult to dismiss a teacher for any reason during this period. In his account of the role of district inspectors, Mr Holloway noted that unsatisfactory teachers were an inspector’s biggest challenge.127 Mr Holloway stated that while teachers could theoretically be dismissed, in practice it was impossible.128 Instead, inspectors were to show tolerance and encouragement towards teachers.129

A culture of authority, reputation and efficiency

It appears that the culture of the education system in Victoria from the 1960s to the early 1990s had a strong emphasis on efficiency, protecting the education system’s reputation and maintaining public confidence. The safety and wellbeing of students was not a focus at the time. Such a culture was not consistent with taking action against teachers in relation to allegations of child sexual abuse. In this regard, Dr Howes in his witness statement referred to anecdotal evidence of a former district inspector that ‘the culture of responding to sexual abuse in a pro-active way was almost non-existent’.130 This anecdotal evidence is consistent with the evidence heard by the Board of Inquiry and the substantial body of material considered by the Board of Inquiry as part of its work.

At the turn of the twentieth century, reforms to the education system primarily targeted improving school efficiency, student learning and the status of teachers. The 1960 report of the Committee on State Education in Victoria largely focused on efficiency measures, noting that population growth had rapidly expanded and schools were facing severe staffing shortages.131 It is telling that the report did not consider in any depth the wellbeing and safety of children.

Public sector legislation from the 1960s to the early 1990s also facilitated a culture that emphasised structure and efficiency rather than the safety or wellbeing of students. The Public Service Act 1974 (Vic) made no mention of values or morality, and was heavily focused on defining powers and structures.132 In contrast, the equivalent legislation today, the Public Administration Act 2004 (Vic), is underpinned by a set of principles that promote integrity, accountability and transparency.

Overall, the culture of the education system in this period appears to have been focused on managing demand and school performance, with little attention given to guarding against or responding to child sexual abuse in schools.

Furthermore, it must be remembered that during the 1960s and the 1970s, government schools and teachers held considerable institutional authority. Similar to societal attitudes within the family home, the social norms of this time dictated adult authority within schools. As a result, children were expected to be compliant and not question adults.133

These beliefs brought with them a hierarchical culture that prioritised the position and voice of teachers and other adults over children. Research on organisational cultures conducted for the Royal Commission found that when organisational cultures ‘support the assumption that children are untrustworthy, staff members will be less likely to believe victims who report child sexual abuse’.134

The Royal Commission’s report also observed that children in school settings often experienced corporal punishment and emotional abuse, which was normalised, noting that ‘[a] culture of physical and emotional abuse in schools can normalise all forms of abuse, creating fear of ramifications for speaking out or resisting’.135

Teacher transfers

As part of the culture of the education system, it appears that the use of teacher transfers was commonplace in the management of allegations of child sexual abuse in Victorian government schools.

Dr Howes, in his evidence, referred to anecdotal evidence from a district inspector who said that district inspectors would move teachers between schools in response to allegations of child sexual abuse.136 Dr Howes gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that this practice was characterised as ‘managing the incident’, rather than being a decision made through the formal disciplinary process.137

It appears the reasons for such transfers were generally known only by the principal of the first school, the district inspector and a small number of other department staff, and were not disseminated more broadly within the Department.138 Dr Howes gave evidence that the district inspector was not required to notify the receiving school or its principal as to the reason for the teacher’s transfer.139

Dr Howes referred to anecdotal evidence from a former district inspector that the culture in the 1970s was to ‘consume our own smoke and try to solve problems when they arise as quickly as possible’.140 In providing evidence to the Board of Inquiry, Dr Howes confirmed that this was ‘illustrative of the way in which matters were handled’ at the time.141 Dr Howes went on to say that one result of this approach was that there was no ‘imperative’ to undertake a ‘thorough investigation’.142

As previously noted, the 1882 Royal Commission into the Administration, Organisation, and General Condition of the Existing System of Public Instruction also found that it was common for schools to transfer teachers alleged to have committed child sexual abuse to another school or position.143

Dr Howes noted that there was a distinct shift in culture relating to the handling of child sexual abuse matters in schools in the early 1990s. Teachers were routinely directed to take leave without pay while allegations were being investigated or after a charge was laid by police. In some cases teachers resigned when allegations were made.144 There was also a considerable increase in the number of primary school teachers dismissed in the 1990s compared with previous decades.145

The settings, structures and practices outlined in this Chapter formed the basis upon which the Department handled child sexual assault reports and disclosures between 1960 and 1999.

Chapter 10 Endnotes

- Education Act 1958 (Vic) s 21, as enacted.

- Education Act 1958 (Vic) s 4, as enacted.

- Education Act 1958 (Vic) s 4, as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 4(2), as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 73(a)–(c), as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 5, as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 26, as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 26(2), as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 48(3), as enacted.

- Education Act 1958 (Vic) s 37, as enacted.

- Education Act 1958 (Vic) ss 52A, 52L(1), as amended by Education (Teachers Registration) Act 1971 (Vic) s 5.

- Regulations General Instructions and Information 1962 (Vic) reg IV (1)(a), 26.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 2.

- Education Act 1958 (Vic) s 14(1), as amended by Education (School Councils) Act 1975 (Vic) s 2(1).

- Regulations General Instructions and Information 1962 (Vic) reg XVII (2)–(3).

- Board of Inquiry into Certain Aspects of the State Teaching Service (Report, 1971) 9.

- Board of Inquiry into Certain Aspects of the State Teaching Service (Report, 1971), 63 (appendix 3); Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) ss 4(2), 48(3), as enacted; Education Act 1958 (Vic) s 37, as enacted.

- ‘What is the Difference between Policy, Act, and Legislation in Australia?’, Parliamentary Education Office (Web Page) <https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/your-questions-on-notice/questions/what-is-the-difference-between-policy-act-and-legislation-in-australia#:~:text=A%20policy%20is%20a%20plan,which%20put%20policies%20into%20action>(opens in a new window).

- ‘Delegated Law’, Parliamentary Education Office (Web Page) <https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/how-parliament-works/bills-and-laws/delegated-law>(opens in a new window). See e.g.: Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(10); Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(1), as enacted.

- Document prepared by the Victorian Department of Education in response to a Notice to Produce, ‘Administrative and Legal Arrangements between the Department and Government Schools in Relation to the Employment of School-based staff between 31 January 1960 and 31 December 1979’, 5 October 2023, 3–4 [5].

- Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(10)–(11); Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(1), as enacted.

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 11 [46]. Note: This is the time period that was reviewed by the Department in preparing its responses to Notices to Produce in October 2023. At this time, the Department had information that 1984 was the last known date of offending by any of the relevant employees. The Board of Inquiry has heard from victim-survivors who allege that they were sexually abused as children after 1984.

- Education Act 1958 (Vic) s 4(2), as amended by Education and Teaching Service (Amendment) Act 1967 (Vic) s 2(2)(b).

- Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(11).

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(1), as enacted. An officer means an ‘officer in the public service’.

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(2)(a), as enacted.

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(2)(b), as enacted.

- Transcript of David Howes, 16 November 2023, 184 [38]–[40], 184 [17]–[40].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, 121 [4], 123 [11]–[32].

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(2), as enacted.

- DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961) 41–2.

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-132 [1]–[17]; Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(10).

- Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 reg 2(11); Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-133 [1]–[43].

- Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(11).

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 2.

- David Holloway, The Inspectors: An Account of the Inspectorate of the State Schools of Victoria 1851–1983 (Institute of Senior Officers of Victorian Education Services, 2000) 451; DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961); Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018. In 2018, in the context of civil litigation, the former district inspector prepared a statement for the Department of Education on the role of district inspectors and his experience. This statement was appended to Dr Howes’s witness statement to the Board of Inquiry.

- Education Act 1872 (Vic) s 5, as originally enacted.

- Regulations General Instructions and Information 1962 (Vic) reg IV (1)(a), 26.

- Regulations General Instructions and Information 1962 (Vic) reg IV (1)(b), 26.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 2.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 2.

- David Holloway, The Inspectors: An Account of the Inspectorate of the State Schools of Victoria 1851–1983 (Institute of Senior Officers of Victorian Education Services, 2000) 451.

- David Holloway, The Inspectors: An Account of the Inspectorate of the State Schools of Victoria 1851–1983 (Institute of Senior Officers of Victoria Education Services, 2000) 452.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 2.

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 12 [50]; Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 3.

- DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961) 41–2.

- DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961) 44–6.

- DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961) 45.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector 2018, 3.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector 2018, 3.

- DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961) 42, 45.

- Royal Commission into the Administration, Organisation, and General Condition of the Existing System of Public Instruction (First Report, 1882) 47 [1053].

- DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961) 42.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 3.

- Statement of David Howes, Attachment DH-6, Report of Former district inspector, 2018, 3.

- Transcript of David Howes, 16 November 2023, P-184 [35]–[47].

- Transcript of David Howes, 16 November 2023, P-184 [38]–[40].

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 4(2), as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) ss 4(2)(d), 73(a), as enacted.

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-132 [1]–[17]; Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(10).

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-132 [1]–[17]; Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(10).

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 73(a), as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 73(a), as enacted.

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(2)(b)(ii), as enacted.

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(2)(b)(iii), as enacted.

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(2)(v), as enacted; Evidence Act 1985 (Vic), ss 14–16, as enacted.

- Public Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 55(2)(v), as enacted; Evidence Act 1985 (Vic), ss 14–16, as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 73, as enacted.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 73, as enacted.

- Government of Victoria, Strategies and Structures for Education in Victorian Government Schools (White Paper, 1980).

- ‘Teachers Tribunal’, Public Record Office Victoria (Web Page) <https://researchdata.edu.au/teachers-tribunal/491699>(opens in a new window) Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 11 [48].

- Education Service Act 1981 (Vic), as amended by the Teaching Service Act 1983 (Vic) s 14.

- ‘About the Merit Protection Boards’, VIC.GOV.AU (Web Page, 14 November 2023) <https://www.vic.gov.au/merit-protection-boards-about>(opens in a new window).

- Education Department, Report of the Education Department for the Year Ended 30 June 1982 (Victorian Government,1983) 11.

- Victorian Government, ‘Shaping Our Past: School Inspectors in Victoria’ (Video, 10 October 2022) 5:22–5:42 <https://www.vic.gov.au/media/222343>(opens in a new window).

- Children and Young Persons (Further Amendment) Act 1993 (Vic) s 4.

- Government of Victoria, White Paper on Strategies and Structures for Education in Victorian Government Schools (1980) 21; ‘About the Merit Protection Boards’, 14 November 2023, VIC.GOV.AU (Web Page) <https://www.vic.gov.au/merit-protection-boards-about>(opens in a new window); Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 12 [49].

- Statement of Lisa Featherstone, 5 December 2023, 7 [35]–[36].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-129 [40]–[42].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-134 [1]–[9].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-126 [15]–[18].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-126 [20]–[22]; Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 9 [35].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-127 [5]–[7]; Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 9 [37].

- Transcript of Jenny Atta, 17 November 2023, P-217 [2]–[3].

- Transcript of Jenny Atta, 17 November 2023, P-217 [3]–[6].

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 13 [54].

- Transcript of Jenny Atta, 17 November 2023, P-224 [30]–[33].

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) vol 13, 132, 134.

- Regulations and General Instructions and Information 1962 (Vic) reg IV (1)(d).

- DG Ball, KS Cunningham and WC Radford, ‘Supervision and Inspection of Primary Schools’ (ACER Research Series No 73, 1961) 149–50.

- Record of interview between a chartered loss adjuster and a former district inspector, undated, 6.

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 19(1)(2).

- See e.g.: Report of the Teachers Tribunal for the Year 1980–81 (Report, 1981) 7.

- Victorian Teachers’ Union, Letter to the Secretary, Teachers’ Tribunal, 7 June 1973.

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 10 [38]–[40]; Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-128 [16]–[29].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-128 [22]–[46], P-129 [1]–[16].

- Teaching Service (Governor in Council) Regulations 1958 (Vic) reg 2(11).

- Transcript of Jenny Atta, 17 November 2023, P-216 [44]–[46].

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) vol 13, 188.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) vol 13, 189.

- Document prepared by the Victorian Department of Education in response to a Notice to Produce, ‘Administrative and Legal Arrangements between the Department and Government Schools in Relation to the Employment of School-based Staff between 31 January 1960 and 31 December 1979’, 5 October 2023, 9 [47].

- Document prepared by the Victorian Department of Education in response to a Notice to Produce, ‘Administrative and Legal Arrangements between the Department and Government Schools in Relation to the Employment of School-based Staff between 31 January 1960 and 31 December 1979’, 5 October 2023, 9 [47].

- Teaching Service Act 1958 (Vic) s 54(2), as enacted.

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 14 [59(a)].

- Royal Commission into the Administration, Organisation and General Condition of the Existing System of Public Instruction (First Report, 1882) 47.

- Royal Commission into the Administration, Organisation and General Condition of the Existing System of Public Instruction (First Report, 1882) 47 [1049].

- Transcript of David Howes, 16 November 2023, P-181 [35]–[36].

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 14 [59(a)].

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 13 [54], 14 [55].

- Police officers completed ‘crime reports’ when a crime of any type was reported to Victoria Police. The reports recorded information about crimes, victims of crime and perpetrators of crime. The Victoria Police Manual (1957 Edition) Consisting of Regulations of the Governor in Council Determination of the Police Service Board and Standing Orders of the Chief Commissioner of Police (1957) 94B–95; Victoria Police Manual (22 December 1997) 2-30 [2.6.8]; Victoria Police Manual (10 June 1997) 2-29–2.30 [2.6.8].

- Eileen Munro and Sheila Fish, Hear No Evil, See No Evil: Understanding Failure to Identify and Report Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Contexts (Report, September 2015) 27.

- State Services Authority Victoria, Organisational Change: An Ideas Sourcebook for the Victorian Public Sector (Sourcebook, 2013) 5.

- Eileen Munro and Sheila Fish, Hear No Evil, See No Evil: Understanding Failure to Identify and Report Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Contexts, (Report, September 2015) 6, 26.

- Eileen Munro and Sheila Fish, Hear No Evil, See No Evil: Understanding Failure to Identify and Report Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Contexts (Report, September 2015) 6.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) vol 13, 13.

- Statement of Patrick O’Leary, 15 November 2023, 2 [10]–[11]; Statement of Leah Bromfield, 23 October 2023, 4 [15]–[16]; Statement of Rob Gordon, 22 November 2023, 6 [30].

- Statement of Leah Bromfield, 23 October 2023, 5 [24] – 6 [25].

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Population Size and Growth’, 24 May 2012, 1301.1 Year Book Australia, 2012 (Web Page) Table 7.3 <https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1301.0~2012~Main%20Features~Population%20size%20and%20growth~47>(opens in a new window).

- ‘Victoria’s Historic Population Growth: European Settlement to Present 1836–2011’, Planning Victoria (Web Document, 2011) 2 <https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/word_doc/0027/29295/accessible-version-of-Victorias-historic-population-growth.docx>(opens in a new window).

- Committee on State Education in Victoria, Report of the Committee on State Education in Victoria (1969) 4521 [2]. <https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/4afdae/globalassets/hansard-historical-documents/sessional/1969/19690501-19690507-hansard-combined2.pdf>(opens in a new window).

- David Holloway, The Inspectors: An Account of the Inspectorate of the State Schools of Victoria 1851–1983 (Institute of Senior Officers of Victoria Education Services, 2000) 449.

- Barry Lachlan Archibald, ‘A History of Inspection in Victorian Colonial/State Government Schools: 1852–2021’ (DPhil Thesis, Charles Sturt University, May 2017) 260.

- Committee on State Education in Victoria, Report of the Committee on State Education in Victoria (1960) 122 [363] <https://digitised-collections.unimelb.edu.au/items/88de22d4-42b8-5da7-a2e1-1a74e91b1f28>(opens in a new window).

- Committee on State Education in Victoria, Report of the Committee on State Education in Victoria (1960) 122 [363] <https://digitised-collections.unimelb.edu.au/items/88de22d4-42b8-5da7-a2e1-1a74e91b1f28>(opens in a new window).

- Employment, Workplace Relations and Education References Committee, Parliament of Australia, Inquiry into Commonwealth Funding for Schools (Report, August 2004) 4–5 [1.7].

- Bob Bessant and Andrew David Spaull, Teachers in Conflict (Melbourne University Press, 1972) 55.

- David Holloway, The Inspectors: An Account of the Inspectorate of the State Schools of Victoria 1851–1983 (Institute of Senior Officers of Victoria Education Services, 2000) 12.

- David Holloway, The Inspectors: An Account of the Inspectorate of the State Schools of Victoria 1851–1983 (Institute of Senior Officers of Victoria Education Services, 2000) 12.

- David Holloway, The Inspectors: An Account of the Inspectorate of the State Schools of Victoria 1851–1983 (Institute of Senior Officers of Victoria Education Services, 2000) 12.

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 12 [53(a)].

- Committee on State Education in Victoria, Report of the Committee on State Education in Victoria (1960) 7 <https://digitised-collections.unimelb.edu.au/items/88de22d4-42b8-5da7-a2e1-1a74e91b1f28>(opens in a new window).

- Public Service Act 1974 (Vic), as enacted.

- Statement of Katie Wright, 23 October 2023, 9 [41].

- Donald Palmer, Final Report: The Role of Organisational Culture in Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Contexts (Report, December 2016) 62; Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) vol 13, 133.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) vol 13, 143.

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 12 [53(a)].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-124 [23]–[26].

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 12 [53(a)].

- Transcript of David Howes, 15 November 2023, P-125 [7]–[23].

- Transcript of David Howes, 16 November 2023, P-185 [33]–[35].

- Transcript of David Howes, 16 November 2023, P-185 [27]–[30].

- Transcript of David Howes, 16 November 2023, P-185 [36]–[39].

- Donald Palmer, Final Report: The Role of Organisational Culture in Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Contexts (Report, December 2016) 31–2; Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) vol 13, 167.

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 13 [53(f)].

- Statement of David Howes, 3 November 2023, 13 [53(f)].

Chapter 11

The alleged perpetrators

Introduction

As set out in Chapter 3, Scope and interpretation(opens in a new window), the Board of Inquiry has identified six relevant employees within scope of its Terms of Reference. They are considered relevant employees as they were employed at Beaumaris Primary School and allegedly sexually abused students at this school between 1960 and 1979. Based on the amount of information available to the Board of Inquiry, this Chapter focuses on four of the six relevant employees, referred to as alleged perpetrators: Darrell Ray, Wyatt, David MacGregor and Graham Steele. ‘Wyatt’ is a pseudonym — he cannot be named for legal reasons.

This Chapter includes narratives on each of these alleged perpetrators. The narratives include information about their employment history and criminal records, what victim-survivors told the Board of Inquiry about them, and the Department of Education’s (Department’s) knowledge of and response to their behaviour.

These narratives have informed the Board of Inquiry’s analysis of and findings about the Department’s response, as set out in Chapter 13, System failings(opens in a new window).

The victim-survivors

The Board of Inquiry heard directly from dozens of victim-survivors whom Mr Ray, Wyatt, Mr MacGregor or Mr Steele allegedly sexually abused. Some victim-survivors shared experiences of sexual abuse by more than one of these alleged perpetrators. The Board of Inquiry also heard from secondary victims about their loved ones’ experiences of child sexual abuse.

In describing the accounts of victim-survivors shared with the Board of Inquiry, it is pertinent to observe there are likely to be people with relevant information who (for various reasons) did not come forward.

The child sexual abuse as described to the Board of Inquiry

The vast majority of the victim-survivors who engaged with the Board of Inquiry shared experiences of sexual abuse as young boys. As discussed earlier in this report, the Board of Inquiry also heard from some victim-survivors that they had been sexually abused as young girls. In most cases, victim-survivors said they had been sexually abused in the middle to late years of primary school.

The Board of Inquiry was told about child sexual abuse taking place in school settings, such as in classrooms and libraries; at sporting events and facilities; and during camps. The Board of Inquiry was also told about child sexual abuse occurring in the alleged perpetrators’ cars, houses and during weekends away.

The Board of Inquiry heard from victim-survivors about child sexual abuse occurring when they were alone, or when the alleged perpetrator deliberately separated them from other children and adults. In other cases, victim-survivors recalled the sexual abuse occurring in front of other children. Some victim-survivors recalled that the child sexual abuse occurred once, but others recalled it occurring over a sustained period of time.

The sexual abuse as recounted by victim-survivors comprised different kinds of conduct. This included victim-survivors having their genitals or other parts of their bodies touched or rubbed, being made to touch the alleged perpetrator’s genitals or watch them masturbate, and being penetrated by the alleged perpetrator.

The Board of Inquiry identified 24 schools as falling within its scope. Of those who engaged with the Board of Inquiry, a higher number of victim-survivors shared experiences of child sexual abuse at Beaumaris Primary School than at any of the other schools.

All forms of child sexual abuse are traumatic. The personal experiences of victim-survivors and secondary victims is included in Part B(opens in a new window).

The alleged perpetrators

This section provides detail on four of the six relevant employees, referred to as alleged perpetrators: Mr Ray, Wyatt, Mr MacGregor and Mr Steele.

Three of these alleged perpetrators — Mr Ray, Wyatt and Mr MacGregor — have been convicted of child sexual abuse offences. In addition to these convictions, many more victim-survivors have engaged with the Board of Inquiry about child sexual abuse allegedly perpetrated by the four men.

Based on victim-survivors and secondary victims who have engaged with the Board of Inquiry, and materials from the Department and Victoria Police, the Board of Inquiry is aware of the following number of allegations of child sexual abuse in relation to each alleged perpetrator:

- Mr Ray: allegations of child sexual abuse relating to 60 individuals

- Wyatt: allegations of child sexual abuse relating to 28 individuals

- Mr MacGregor: allegations of child sexual abuse relating to 13 individuals

- Mr Steele: allegations of child sexual abuse relating to eight individuals.

Connections between the alleged perpetrators

The alleged perpetrators were all employed at Beaumaris Primary School for two years (1971 and 1972). The Department’s records show that Mr MacGregor was on leave in 1971, however Mr MacGregor told the Board of Inquiry he was granted leave in 1971 but took leave in 1972. What is clear is that in 1971 and 1972 the alleged perpetrators were all employed as teachers at Beaumaris Primary School, and for one of those years Mr MacGregor took leave.1 Over the course of their careers, the alleged perpetrators worked across a total of 23 other government primary schools that fall within the Board of Inquiry’s scope. These 23 schools, as well as Beaumaris Primary School, are within scope to the extent the child sexual abuse a victim-survivor shared with the Board of Inquiry involved one of the alleged perpetrators. Most of these schools are located in the south-east region of Melbourne.

Not only were the alleged perpetrators employed together at Beaumaris Primary School for a time, at other times they worked at schools in close proximity to one another. Mr Ray and Mr MacGregor also attended Toorak Teachers’ College at the same time between 1961 and 1962.2

Information also suggests that some of the alleged perpetrators had connections outside of school.

Many people recalled that Mr Ray and Mr Steele were good friends. Former teachers at Beaumaris Primary School described Mr Ray and Mr Steele as ‘great mate[s]’.3 One teacher recalled that Mr Ray and Mr Steele would take boys ‘off for bashes [of cricket] on Fridays, and occasionally on weekends’.4

The Board of Inquiry also understands that Mr Ray and Mr Steele went on a holiday overseas for five months, and travelled together in a campervan.5

A former teacher at Beaumaris Primary School recalled that Mr Ray, Wyatt and Mr Steele were ‘close’, likely due to their interest in sport.6

The Board of Inquiry received information that suggested that Wyatt was close friends with another alleged perpetrator, based on their personal connections and shared activities outside of school. Due to Wyatt’s Restricted Publication Order, further detail cannot be included in this report.

The Board of Inquiry was also told that two of the alleged perpetrators had a familial relationship.

It is notable that the alleged perpetrators worked at Beaumaris Primary School at the same time, worked in other schools within close proximity to one another, and some had connections with one another outside of school. Professor Leah Bromfield, Director of the Australian Centre for Child Protection and Chair of Child Protection, University of South Australia, gave evidence to the Board of Inquiry that if an individual is perpetrating child sexual abuse in an institution, this may ‘create a culture … which assists others to overcome internal inhibitions they may have to sexually abusing a child’ — for example, normalising the child sexual abuse or decreasing the fear of consequence of being caught.7 Relevantly, one victim-survivor recalled that Mr Ray sexually abused him while Wyatt observed.8

The four alleged perpetrators were also all involved in sport, through sports coaching at the schools or through sporting organisations.9 Some victim-survivors shared that the alleged perpetrators were respected for their sport coaching ability, and they would use these positions to bring children into their orbit.10 For further detail, see Chapter 12, Grooming and disclosure(opens in a new window).

Use of the term ‘alleged perpetrator’

Objective (a) of the Board of Inquiry’s Terms of Reference is to ‘establish an official public record of victim-survivors’ experiences of historical child sexual abuse’.11 Consistent with this, the Board of Inquiry shares the following narratives as part of the public record of victim-survivors’ experiences, but does not make any findings of fact in relation to them. It has not examined or tested the information in order to make any findings, nor has it applied any legal tests that may be required to make findings in legal proceedings.

The Board of Inquiry has relied on documents from the Department and Victoria Police in relation to the employment history and criminal records of the alleged perpetrators. Due to historical record-keeping practices and the past reliance on hard copy material, the amount of available information used to prepare these narratives varies, and in some instances may be inconsistent with the recollections of and information held by victim-survivors. In addition, on 12 September 1994, there was a fire at Beaumaris Primary School that resulted in the loss of some school records dating back to when the school opened in 1915.12 An affected community member with a connection to the school told the Board of Inquiry it was unlikely the fire would have destroyed any relevant records as the office was small and everything was sent to the Department.13

In preparing the narratives, the Board of Inquiry has not examined civil claims against the Department in relation to the alleged perpetrators. In accordance with its Terms of Reference, the Board of Inquiry did not inquire into:

- the response of the State of Victoria (including the Department and its staff) to any complaints (other than in relation to the Department’s response at or around the time of the alleged child sexual abuse, consistently with clause 3(c) of the Terms of Reference)

- legal proceedings or legal claims in relation to incidents of historical child sexual abuse in a government school

- compensation or redress arrangements, including the settlement of any civil claims.

In addition, and in line with its Terms of Reference, the Board of Inquiry also seeks to avoid causing prejudice to any current or future criminal or civil proceedings. Any consideration given by the Board of Inquiry to the content of civil claims would risk causing prejudice to such civil and criminal proceedings.

Alleged perpetrator narrative: Darrell Ray

Teaching history